Prominent Turkish journalist is jailed after quoting proverb deemed ‘insulting’ to Erdogan

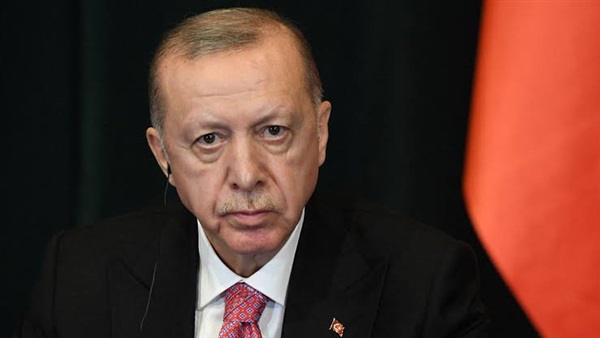

A prominent Turkish journalist was jailed Saturday after being charged with “insulting” President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in what her lawyer and media advocacy groups described as an unusually harsh measure that could further chill press freedoms.

The charges against the journalist, Sedef Kabas, came after she quoted what she said was a proverb while appearing as a guest on a news show last week discussing Erdogan and political polarization in Turkey. The proverb, which she also posted on Twitter, said: “When the ox goes to the palace, he does not become a king. But the palace becomes a barn.”

Tens of thousands of people are investigated every year for insulting the president, under a long-standing section of the criminal code that Erdogan, in recent years, has vigorously enforced against political opponents as well as ordinary citizens. Figures by Turkey’s Justice Ministry showed that prosecutors pursued more than 31,000 cases of insulting the president in 2020. Nearly a third of those cases resulted in formal charges, it said.

Fahrettin Altun, a spokesman for Erdogan, called Kabas a “so-called journalist” on Twitter and said her comments had “no goal other than spreading hatred.”

“The honor of the presidency is the honor of our nation,” he wrote.

Ugur Poyraz, her lawyer, called the decision to remand Kabas, “strange” and “a very serious and big mistake.”

“There is no suspicion of her leaving the country, nor is there any suspicion of obfuscation the evidence, nor is there any question of her not going to authorities when she is summoned,” he said Saturday in an interview on Turkey’s Halk TV channel.

Erol Onderoglu, the Turkey representative for Reporters Without Borders, said that since Erdogan was elected president in 2014, the group had tracked 200 cases in which media workers had been investigated for insulting him. At least 70 of those cases had resulted in convictions, he said.

The decision to remand Kabas was surprising in part because the climate for media workers had eased somewhat, after years in which Turkey was known as one of the world’s leading jailers of journalists, Onderoglu said. Though reporters were still regularly prosecuted on terrorism and other charges, Turkish courts in the last year had appeared more willing to acquit them, he said. At the same time, the government was resorting to other punishments — like travel bans and regular check-ins at police stations — rather than prison time.

A backdrop to the arrest is the rancorous political atmosphere in Turkey, as jockeying begins ahead of presidential elections scheduled for next year amid a severe economic crisis that has put the government on the defensive and made it perhaps anxious to change the subject. In addition to Kabas, Erdogan and his allies have in recent weeks harshly attacked Sezen Aksu, a revered Turkish singer, accusing her of defaming Islam because of a lyric in a song she released in 2017 that has recently resurfaced.

Kabas has worked at CNN in Atlanta, several Turkish television channels and written six books on journalism, according to a biography on her website. Onderoglu said it was possible, as in other “insult” cases, that the authorities could release her pending trial.

But “the political climate has changed,” he said. “We are really concerned about the most draconian and disproportionate measures