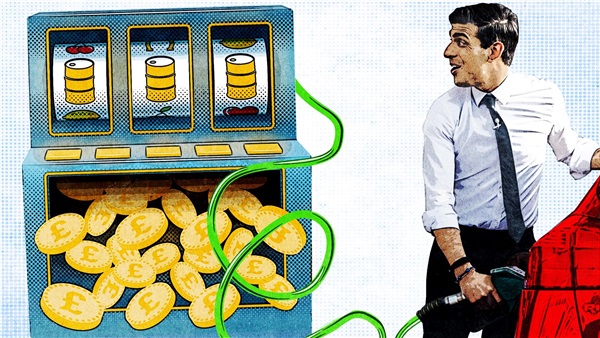

Who’s making the money on fuel — and how high could prices go?

Rachel Adam-Smith cannot live without her car. Over the next two weeks she must ferry her disabled daughter to ten different medical appointments. There are no trains serving her home in Boston Spa, a town between York and Leeds: the hospital is half an hour away.

“I was at the pump the other day and I just couldn’t fill all the way up,” she said. “Firstly, the thought of paying £100 for a tank of petrol was just too much, and secondly, I simply couldn’t afford it.”

The 45-year-old was lent a Kia Sportage — a large family car big enough for a wheelchair — by the charity Motability. “The boot space is great for the chair, but that car gets through a lot of petrol. A tiny Toyota Yaris wasn’t really an option for us.

“My fuel bill used to be about £200 a month. Now it’s £300 to £400. It’s not like I can change my financial situation — I’m a full-time carer for my daughter, who is 18. The pump in the village here is £1.99 a litre.”

Driving is often seen as a luxury rather than a necessity. Yet 68 per cent of people in Britain used a car to get to work in 2019, compared with 11 per cent who took the train. For those in more rural areas, the creeping price of petrol and diesel makes inflation considerably more brutal.

Electric and hybrid sales may be soaring, but petrol and diesel models still make up the majority of cars on the roads. Oil prices have surged globally, yet Britain has among the most expensive fuel costs in Europe. A litre of unleaded petrol costs an average of £1.83, compared with £1.66 in Italy and £1.08 in Hungary.

Today it can be revealed that Kwasi Kwarteng, the business secretary, has written to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) asking them to launch an investigation of the fuel market over concerns that drivers are not getting a fair deal. He has also asked for a longer-term study under the Enterprise Act 2002 to explore whether the retail fuel market has adversely affected consumer interests.

Government sources claim that its 5p cut to fuel duty has not been passed on to consumers everywhere. Yet data suggests the Treasury has taken in billions in tax revenues since the war in Ukraine started.

Petrol stations are the obvious objects of ire, particularly when prices go up fast enough to see. The average cost of a litre of unleaded petrol is £1.83, and £1.89 for diesel, according to the RAC — yet prices above £2 have been seen at motorway services near Sunderland, Wetherby, Chippenham and Burton-in-Kendal. In Chelsea, west London, one forecourt was seen charging £2.39p per litre on Friday.

Why do some petrol stations charge more than others? “Different pumps have different delivery costs,” said Gordon Balmer, executive director of the Petrol Retailers Association. Rural stations tend to be more expensive for this reason.

Some of the most expensive pumps are to be found at motorway services: their operators argue that they have lots of other services to maintain, including access roads and parking. Critics argue that they have a captive audience, so can charge what they like.

Another reason why price changes do not keep in step is that some pumps buy their petrol on a fortnightly price, while others buy it on a daily tariff. This means that some pumps are reflecting the price two weeks ago, rather than the day before.

How much money are petrol stations actually making? It depends who you ask, but it is no more than a few pence per litre. According to the RAC, 2.76p per litre is the profit for retailers on petrol, and 6.67p per litre for diesel.

However, pointing to separate figures, Balmer says many independent retailers are not making any profit at all. In fact they are losing money with every litre sold, and are forced to make up the cost through selling other products. “Our retailers are really struggling,” he said.

Retailers have been accused of not passing on the 5p cut to fuel duty imposed on March 23, or 6p after VAT. A week later, pump prices had fallen by just 3.8p, and diesel 2.3p. However, fuel is now around 15p more expensive than before the cut was imposed. The government is making more money from petrol now than it was before the tax cut.

Fuel is doubly taxed. Duty is charged at a flat amount, which was cut from 57.95p to 52.95p per litre. Then the Treasury takes a further 20 per cent — that is, VAT — at every fill-up.

Duty may have fallen, but because the price of petrol and diesel has increased so much, VAT receipts have soared. An analysis of sales and pricing data suggests the government is raking in about £77 million a day in both duty and tax receipts, compared to £72 million the day before Russia invaded Ukraine. Since then, the government has raised an estimated £7.9 billion in fuel receipts, 12 per cent more than the same period last year.

The amount of tax — currently 83p per litre, or about 46 per cent of the total — is towards the upper end of European countries: lower than France, at 50 per cent, and Germany, at 49 per cent, but above the other EU states and the US.

Many think the government should forgo a larger share of fuel duty. Howard Cox, founder of the FairFuelUK Campaign, is calling for a 20p cut in fuel duty. “I do think it’s feasible. I’ve got a lot of backbench support for this,” he said.

Decisions that would have been unpopular months ago suddenly seem palatable. Nathan Piper is head of oil and gas research at Investec. “The difficulty here is that in the context of net zero, reducing taxes on fossil fuels encourages consumption,” he said.

Professor Jonathan Portes was chief economist at the Cabinet Office between 2008 and 2011. “The short answer is that this is largely about global oil prices. Whatever is happening at petrol stations and in the retail market is not a key driver. The people who are making massive profits are the oil companies.”

The oil giants have made a fortune from the war in Ukraine. They reported profits of $93 billion (£76 billion) in the first quarter of 2022. Shell alone made profits of $9 billion, three times the equivalent last year.

BP’s chief financial officer, Murray Auchincloss, told investors in February that the company was likely to get “more cash than we know what to do with” as a result of rising prices.

“We have some idea of why that has happened,” said Portes. “Prices have gone up but oil producers have not, in contrast to previous episodes, increased supply. They’re holding back. It’s not because there’s a global conspiracy — they’re just not sure how long it’s going to last.”

Many think the price of oil, currently above $120 a barrel, will only get higher. Russia is, after all, the second-largest exporter of crude oil in the world.

“We’re only just starting to see the effects of sanctions on Russia,” said Piper. “EU sanctions are being phased in by the end of 2022, and haven’t bitten yet. What we’re seeing is the result of the drop in diesel production, plus the global economy coming back to life after Covid.” He has previously suggested petrol could get as expensive as £2.50 a litre.

After pressure from Cox and Robert Halfon, the MP for Harlow, the Competition and Markets Authority is set to investigate whether the 5p cut in fuel duty is being passed on. “Working out the profits made by oil companies is almost impossible,” said Cox.

At this stage, however, 5p on the litre is a mere drop in the ocean.