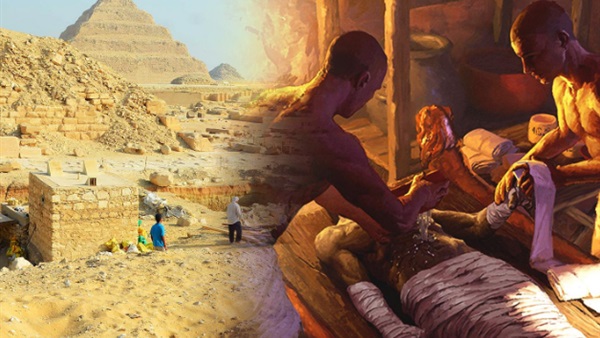

Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Egyptian Trade Networks through Mummies

Recently, researchers have uncovered new information about

the trade networks of ancient Egypt by studying the mummies that were produced

thousands of years ago. The study focuses on a workshop that was located near

the necropolis of Saqqara, a prominent burial ground in ancient Egypt. The

workshop was discovered in 2016 and, when it was excavated, researchers found

dozens of ceramic vessels containing the substances used in the mummification

process.

To the surprise of the researchers, many of the substances

used for mummification were not sourced from within Egypt. The analysis of the

contents of the pots showed that various substances were used for different

parts of the body, such as pistacia resin and castor oil for the head, and

other mixtures for washing and softening the skin. Some of these materials were

transported from great distances, such as the Mediterranean, the Levant, and

the Dead Sea. The study also found two previously unseen substances: dammar gum

and elemi resin.

Elemi resin appears to have come from equatorial or southern

Africa or from South or Southeast Asia. The trees that produced dammar grow

only in southern India, Sri Lanka, and tropical Southeast Asia. This discovery

suggests that the demand for these exotic resins was significant and may have

played an important role in the early development of global trade networks.

The ancient Egyptians mummified their dead for over 3,000

years, hoping to ensure that their souls would have a permanent resting place.

The process of mummification involved a series of rituals, including prayers,

incense burning, anointing, and wrapping of the body. This process was thought

to transform the deceased from an earthly being to a divine being.

Previously, researchers studying mummification methods had

limited information available to them, relying primarily on pictorial evidence

and references in Egyptian texts and accounts from Greek writers such as

Herodotus. However, the discovery of the workshop jars has provided new insight

into the mummification process. For example, the substance known as

"antiu" had long been thought to be myrrh or frankincense, but it was

actually a blend of cedar oil, juniper or cypress oil, and animal fats.

The findings of the study have helped to correct

misunderstandings about the mummification process and shed new light on the

trade networks of ancient Egypt. Dr. Susanne Beck, who is leading the

excavation, stated that "we have known the names of many of these

embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered. But

until now, we could only guess at what substances were behind each name."

The discovery of the workshop jars has provided a wealth of new information

that will be valuable to future researchers studying the history and culture of

ancient Egypt.