The Nile: The First Pillar of Egyptian Civilization

"From what age did you start

flowing through the villages?

And by whose hand do you bless

the cities?

Did you descend from the heavens,

or were you sprung

From the lofty gardens, flowing

like sparkling streams?

And through whose eye, cloud, or

flood

Do you overflow and flood the

lands?"

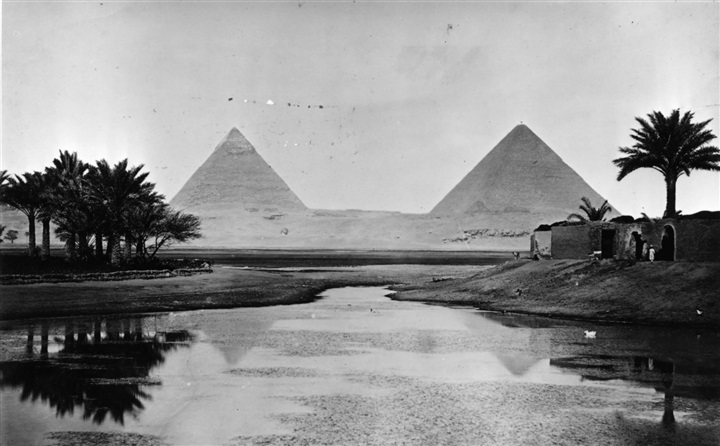

These are the questions posed by

the Prince of Poets, Ahmed Shawqi, and immortalized in song by Umm Kulthum in

praise of the eternal Nile, which has linked earthly life with the afterlife in

the beliefs of ancient Egyptians for millennia. As a result, homes, palaces,

and temples of the gods were often built on the eastern bank of the Nile, while

tombs and funerary temples were located on the western bank.

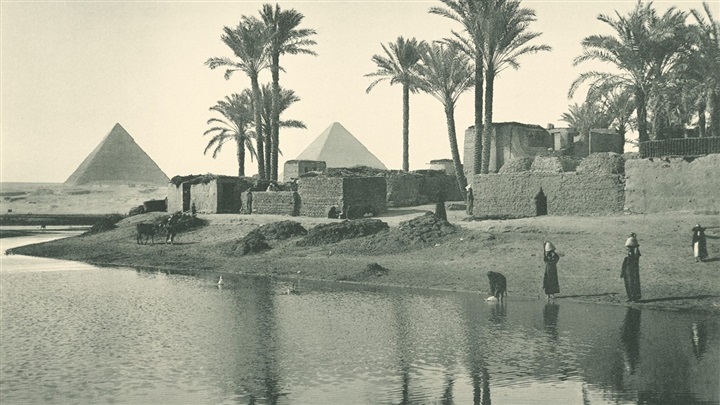

In his book Egypt and the Nile:

Between History and Folklore, Dr. Amr Abdel Aziz affirms that thinkers

throughout history have been captivated by the Nile, constantly describing and

studying its sources, basin, and mouth. This fascination is natural, as anyone

who has lived in Egypt, interacted with its people, visited, or neighbored it

knows that the Nile is the source of Egypt’s wealth and prosperity. It is the

fundamental pillar upon which early Egyptian civilization was built, a

civilization that has impacted the entire world.

It is no surprise that the Nile

has been of paramount interest to Egyptians and others since ancient times, and

no river in the world has had such a profound influence on a region and its

inhabitants as the Nile. In the Book of the Dead, the ancient Egyptian would

swear, "I have not polluted the river’s water," demonstrating the

deep reverence and care they held for this life-giving artery of Egypt.

The Great River

The ancient Egyptians called the

Nile "Atro Aa" or "The Great River" because it was the god

of fertility and abundance, ensuring protection from famine and drought. The

term "Nile" itself originates from the Greek word "Neilos."

The Nile's primary deity was "Hapy," depicted as a full-chested,

full-bellied man, symbolizing the river's bountiful gifts. Additionally, there

was a god of the flood, "Khnum," worshiped in Aswan. As the god of

creation, Khnum was also associated with the flood, which the ancient Egyptians

believed was responsible for creating the fertile Egyptian land.

The exploration of the Nile began

when ancient Egyptians transitioned to agriculture. Although their knowledge of

the river's upper reaches was limited, they quickly connected with the people

and lands inhabiting the Nile Valley to Egypt's south, continuing their efforts

to uncover the river’s mysteries.

Due to their lack of knowledge

about the Nile’s sources in Central Africa, the ancient Egyptians believed that

the river originated from a subterranean cave on the island of Biga in Aswan.

Greek historian Herodotus noted that the chief priest of the goddess Neith in

Sais mentioned the river emerging between two mountains on that island, named

"Krophi" and "Mophi." The river, according to this account,

sprang from between these two peaks. In the Philae Temple in Aswan, the god

Hapy is depicted inside a cave, with a serpent coiled around him, symbolizing

the Nile’s flow from a narrow opening between the snake’s tail and mouth.

Ancient Projects

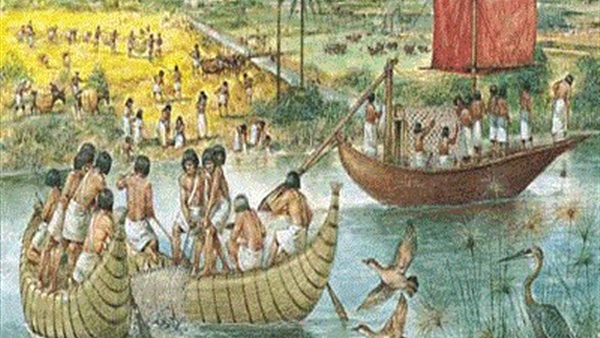

The ancient Egyptians were

diligent in making the most of the Nile’s resources, implementing major

projects during their time. One of these projects was turning the city of

Memphis (now Mit Rahina) into a quasi-island to protect it, a feat achieved by

the first pharaoh of Egyptian history, King Menes.

Additionally, the largest

agricultural project in Egypt’s history was initiated, reclaiming 100,000 acres

of land in what is now Faiyum. This project was undertaken by the pharaohs of

the Middle Kingdom in the 20th century BCE, diverting excess floodwater into

Lake Qarun through a channel still known today as "Bahr Youssef." The

ancient Egyptians also carved a canal through the rocks of the first cataract

east of Sehel Island in Aswan to facilitate the passage of boats. This canal

was named after its creator, King Senusret III, and carried the title

"Beautiful are the Ways of King Khakheperre."

The Flood

In ancient Egypt, the most

significant event linked to the Nile was the arrival of the annual flood, which

the Egyptians marked as the start of their calendar year. The ancient Egyptians

divided their year based on the Nile’s behavior, with the first season being

the flood season. Once the floodwaters receded, the agricultural season began,

followed by the harvest season, which completed the annual cycle.

According to Egyptologist Dr.

Zahi Hawass, the ancient Egyptians closely monitored the river, eagerly

awaiting the months of the flood signaled by the appearance of the star Sirius

in the sky. As the floodwaters arrived, the agricultural year would commence,

and they devised the Nilometer to measure the water level and anticipate the

bounty flowing from the south.

The Nile's Loyalty

For about seven thousand years,

the Egyptians have celebrated the festival of "Wafaa El-Nil" (The

Nile's Loyalty), one of Egypt’s oldest historical festivals, traditionally held

in August (the month of Boona). The term "Wafaa El-Nil" refers to the

Nile's loyalty in delivering the Egyptians bountiful water and silt.

The flood lived on in the

collective memory of the Egyptian people, who continued to celebrate it

annually through the ages, even during periods of foreign rule. The festival of

"Wafaa El-Nil" remained a profound expression of the Egyptian people's

bond with the Nile, deepening their connection to it.

The Bride of the Nile

As the Nile spread life along its

banks, it also inspired various myths and legends, which varied depending on

the era and location. One such legend is the story of the "Bride of the

Nile," which tells of the ancient Egyptians offering a beautiful maiden to

the god Hapy during his festival. The girl, adorned in finery, was thrown into

the Nile as an offering to the god and would marry him in the afterlife. In one

version of the story, when no girls were left, the king’s daughter was the only

choice. However, her maid hid her and instead threw a wooden effigy into the

river, fooling everyone. The maid then returned the girl to her father, who had

fallen gravely ill from sorrow at her supposed death. Thus, the tradition of

throwing a wooden effigy, known as the "Bride of the Nile," into the

river was born.

However, Egyptologists agree that

there is no historical evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians

sacrificed a human "Bride of the Nile" during the festival. Human

sacrifices were never practiced by the ancient Egyptians, and any offerings

made were either animal or symbolic. In her book The Nile in Popular

Literature, writer Ne'mat Ahmed Fouad emphasizes that the story of the Bride of

the Nile has no historical basis, except for the account given by the historian

Plutarch, who wrote that King Egyptus sacrificed his daughter to the Nile upon

the advice of priests to avert disasters befalling the land, later regretting

the act and throwing himself into the river after her.

French researcher Paul Lange, who

dedicated his studies to the Bride of the Nile myth, concluded that the ancient

Egyptians did not throw a living bride into the river. Instead, the Egyptians

celebrated by offering a fish known as "The Atem," whose skeleton

resembles a human’s. Because of this similarity, scholars referred to it as the

"Bride/Lady of the Sea."