The Muslim Brotherhood and “prison literature”… From adversity poems to love letters

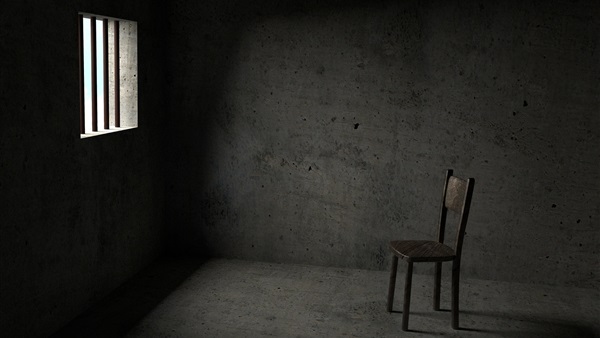

In

the corner of a prison cell sat someone holding a pen and some papers, hastily

scribbling some lines, and then stashing the notes away from guards.

About five or six decades ago, we received

ideas that originated in prisons; Members of the Muslim Brotherhood, founded by

Islamic scholar Hassan al-Banna in 1928, set about writing notes, messages and

diaries from their prison cells. These writings were called “Griefs of

Adversities”.

As Islamic theorist and leading member of

the brotherhood Sayyid Qutb (1906-1967) started doing his time in Liman Tora, a

maximum security prison located south of Cairo. He concluded his vision, as he

addressed the ignorance of the community and the inevitability of clashing with

the ruler.

Qutb’s thoughts remained behind prison

walls since he was sentenced to 15 years in 1955.

In 1959, he finished writing the last 12

parts of his book “Fi Zilal al-Qur'an” (In the Shade of the Qur'an), and

started emending the first 18 parts of the book, which were published between

1952 and 1954.

Qutb managed to share his thoughts with his

prison mate Youssef Hawash as he was receiving treatment at the prison’s

hospital in the early sixties.

Together, Qutb and Hawash, began aspiring

for the foundation of a new Islamic movement. From 1962 to 1964, Hawash started

promoting the movement, while Qutb began communicating with members of the

brotherhood during his time in the exercise yard of the hospital.

Members of the brotherhood started

approaching Qutb to get to know his invitation to the Islamic movement. He

confessed forming groups inside the prison to study his books.

Qutb’s younger sister, Hamida, was known as

“the messages carrier”; she was the link between Qutb and his supporters.

His book “Ma'alim fi'l-Tariq”

(Signposts on the Road, or Milestones), published in 1964, was described as the

constitution of extremist groups; it was written in prison and the brotherhood

categorizes it under “prison literature.”

In his last writing “Limatha A'damuni”

(Why They Executed Me), one penned in the hours before his

execution, Qutb exhorted the assassination of the president, prime minister,

military police director and intelligence director, in addition to a plan to

blow up some public facilities such as power stations and bridges.

Forum

of storytellers

Meanwhile, a stream of the leftist Muslim

Brotherhood feared the spread of Qutb’s ideas that promoted violence,

excommunicated the community and rulers. But second General Guide of the

brotherhood Hassan al-Hudaybi, however, approved printing Ma'alim fi'l-Tariq.

Hudaybi also argued, “Qutb understood that

the Islamic creed la ilaha illa'llah (There is no god but Allah) means

that there is no god on earth but Allah, and that he a god on earth and in

heavens.”

Moreover, Hudaybi sent a message to

imprisoned members of the brotherhood who objected Qutb’s thoughts, saying, “What

Qutb said is the right thing and no Muslim can claim otherwise, however, I just

object the strong expression of his right opinion.”

“There is no need to argue, anyone can

either choose to follow or not to follow Qutb, until our prisoners are

released, and the brotherhood is active again, then we can hold this subject

for discussion to determine what should be said and what should not.”

In 1955, Islamic theologian and the current

chairman of the International Union of Muslim Scholars Yusuf al-Qaradawi used

to recite his poems to the inmates of the Military Prison.

The prison was the forum of storytellers,

and because Qaradawi was not allowed to possess pens or papers, his only way to

preserve his ideas was by reciting stanzas to his cellmates so that they would

transfer them to members of the brotherhood when they get released, in order

for them to get documented and categorized under “Adversity Literature.”

Adversity

Literature

Over twenty years in the Military Prison,

Qaradawy wrote an epic poem of 294 stanzas describing his sorrow and woes.

On the other hand, messages of Muslim

Brotherhood leading activist Kamal al-Sananiri had a romantic trait; during his

time in jail in 1954, he asked proposed to Qutb’s sister, Amina, and she

approved immediately, knowing he was sentenced to death; they were engaged for

about 20 years while Sananiri was in the Military Prison.

“It has been so long, and I pity you for

this suffering, in the beginning of my engagement I told you that I might be

released tomorrow, and I may spend the remaining twenty years here, or time may

end,” Sananiri wrote in one of his messages to Amina. “I would not want to be

an obstacle in the way of your happiness, you are absolutely free to make a

decision that suits your future from now on, and may Allah guide you through

what is best.”

“I chose a hope that I am expecting, the

way of jihad and heavens, solidity and sacrifice, and insisting on what we

pledged with a firm belief without hesitation or regret,” Amina replied.

Former Brotherhood leader Tarek Abul Saad said brotherhood writings in prisons that are known to

us are some poems that were written by brotherhood leaders, some personal

messages, Hudaybi’s “Du'a la quad” (Preachers, not Judges), Qutb’s “Limatha

A'damuni” (Why They Executed Me) and “Fi Zilal al-Qur'an” (In the

Shade of the Qur'an).

Abul Saad said some leaders of the

brotherhood would bribe guards to pass them pens and papers. He also added to Al-Margea

that these writings found their way out of prison through the women, sisters

and lawyers of the brotherhood members during visitations.