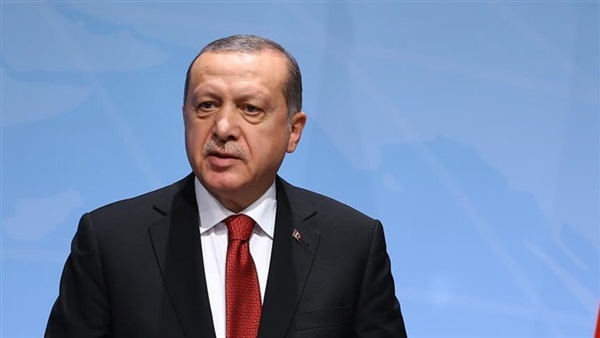

A dictator digging own grave, Erdogan’s policies to draw an end

Recent

changes have affected the opinions of Turkish voters regarding their

representatives in the local elections in favor of the Justice and Development

Party (AKP), putting the Turkish president's future and the country's political

tracks at stake.

Polling

started on June 23 for Turkey's re-run local elections to elect a new mayor for

Istanbul.

Ekrem

İmamoğlu, candidate of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), and Binali

Yıldırım of the AKP, were vying to run the metropolitan municipality of

Turkey’s most populous city after a previous vote on March 31 was annulled by

the country’s top election council.

In

Istanbul, İmamoğlu received 48.8 percent of the vote, whereas Yıldırım got

48.55 percent, according to official figures from the Supreme Election Council

(YSK).

The

YSK ruled in favor of a re-run, with seven votes in favor and four against.

The

results in March were canceled after AKP and its coalition partner, the Nationalist

Movement Party (MHP), appealed to the YSK, citing irregularities and

contradictions with legal measures, which was all pressured by President Recep

Tayyip Erdoğan.

Erdoğan’s

move was heavily criticized by Turkish opposition that described the President’s

interference in the voting process as “dictatorship” and an unusually flagrant

violation to the democratic system of Turkey.

And

by analyzing the situation in Turkey, we find that since Erdoğan’s came to

power, all supervision over his authority was systematically eliminated, but

one form remain, which is the elections that Erdoğan couldn’t escape.

A

study by European Eye on Radicalization said Erdoğan relied in his approach to

attaining power over electoral legitimacy, as he considered it the voices of

the silent majority that was deprived of its rights by religious Turks during

the Ataturkian hegemony.

Istanbul

provides an enormous amount of the cash needed to keep AKP functioning. The

city is governed by a web of pro-AKP businessmen working side-by-side with

state officials to create jobs and services through construction and

infrastructure projects, which boost AKP’s popularity and make both the

businessmen and the AKP wealthy.

It

is, then, a serious blow for the AKP to have lost the Istanbul vote a second

time—and to have lost by such a decisive margin (nearly ten percentage points).

As important as Istanbul is for AKP, Erdogan could have tried to keep more of a

distance, yet he went all-in and it still did no good. Even Fatih, the

ultra-conservative Istanbul district, voted for CHP for the first time in

anyone’s living memory.

There

have been other signs since the election that the AKP is in retreat, and the

opposition has clearly been emboldened. It is an open question how much Erdogan

can be rolled back; he and his loyalists still have control of levers within

the state and outside it that can be used to undermine Imamoglu. And however

far the opposition gets politically, undoing the ideological damage done, in

Turkey and beyond, will take even longer.