Southern Thailand’s forgotten conflict reignites

Last week 15 people were killed and others wounded in an insurgent

attack on a checkpoint in southern Thailand, home to a

long-simmering low-intensity conflict in the country’s historically

violence-plagued Yala province, a report by Soufan group noted.

The attack occurred at a security checkpoint manned by a mixture of volunteer self-defense militias and police officers. In the midst of the operation, insurgents managed to capture weapons and munitions.

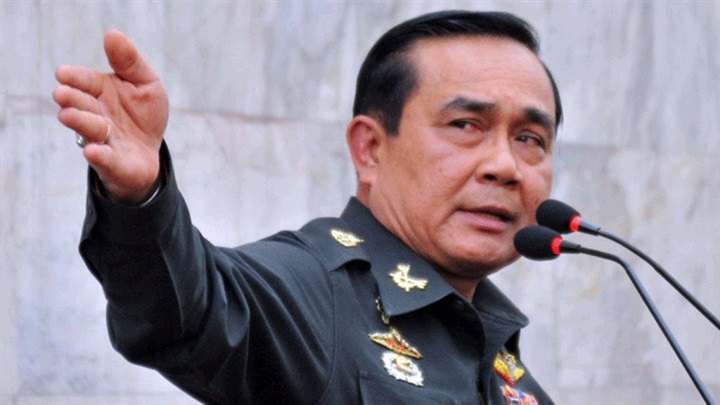

Following the attack, the insurgents, who were armed with assault rifles and other light arms, fled to a rubber plantation located nearby. In response to the ambush, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha met with senior security officials to discuss the Thai military’s force posture in the region.

The attack brought to the fore the armed conflict in southern Thailand, one of the world's most neglected armed conflicts, despite its effects on international security.

The ethnic Malay Muslim insurgency against the Buddhist Thai majority in the southernmost reaches of the country, along the border with Malaysia, is among the least reported on and analyzed conflicts in the world.

Ethnic and religious violence in the southern Thai provinces of Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat dates back to the late 1950s, with the current iteration of violence a phenomenon since 2004, during which time period as many as 7,000 deaths have been attributed to the conflict.

Violence peaked in 2007, and 2019 has seen an ebb in insurgent activity; the past two months have witnessed historic lows in terms of insurgency-related deaths. The Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN), or National Revolutionary Front, was likely seeking revenge for the death of an insurgent, who died while in Thai army custody in August.

Moreover, the report added, locals complain that the government in Bangkok acts with a heavy hand in enforcing language and other laws foreign to the ethnic Malay culture, which is distinct from areas in central and northern Thailand.

Malays constitute 80 percent of the region’s 2 million people. The genesis of the insurgency has been traced back to several prominent madrassas and mosques. While peace talks commenced in 2013, they were abruptly ended by the military.

Since May 2014 the government has stated its willingness to continue negotiations, but has benefitted from a decline in the violence and not had to make any concessions. There are growing concerns that the lack of a framework for peace negotiations and a total dismissal of the insurgents’ grievances by the Thai government could signal a return to more consistent violence in the region.

his violence could include ambushes, the assassination of government officials and civilians, and the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), but also well-planned spectacular attacks designed to grab the attention of the media and government. In previous years, there have been beheadings and bodies burned by the insurgents, consistent with some of the most extreme tactics used by Islamist extremists throughout the world.

Unlike other countries in the region such as the Philippines and Indonesia, Muslim insurgents in southern Thailand have largely remained focused on parochial issues and have not forged links with transnational terrorist groups like al-Qaeda or Daesh.