Yemen's Unique 'Dragon's Blood' Island Under Threat

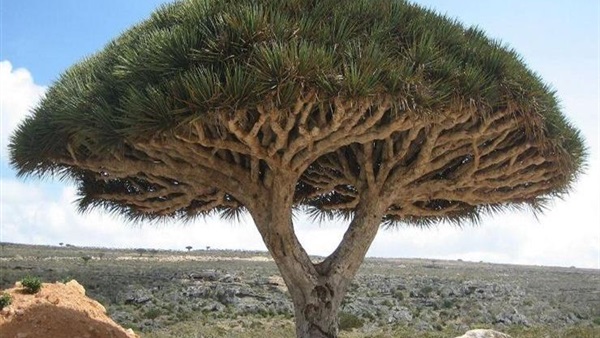

Centuries-old umbrella-shaped dragon's blood trees line the rugged peaks of Yemen's Socotra -- a flagship symbol of the Indian Ocean archipelago's extraordinary biodiversity, but also a bleak warning of environmental crisis.

Forests of these ancient trees are

being decimated by increasingly intense storms, while replacement saplings are

gobbled by proliferating goat herds, leaving the fragile biological hotspot

vulnerable to desertification.

"The trees bring water, so they are so

important," said Adnan Ahmed, a mathematics teacher and tour guide whose

passion is Socotra's famous flora and fauna.

"Without trees, we will be in trouble."

Lying in turquoise seas between

Arabia and Africa some 350 kilometres (215 miles) south of Yemen's coast,

Socotra is home to over 50,000 people and has remained relatively untouched by

the bloodletting of the civil war raging on the mainland.

Naming it a World Heritage site in

2008, UNESCO described the main island as one of the world's "most

biodiversity rich and distinct". It has also been dubbed the

"Galapagos of the Indian Ocean".

Ahmed said islanders traditionally

don't fell dragon's blood trees for firewood, both because they perpetuate

regular rainfall and because its blood-red sap is medicinal.

But scientists and islanders warn

that the trees will largely die out within decades, buckling under pressure

from global warming driving cyclones, as well as invasive species and

overgrazing.

"Goats eat the seedlings, so young trees are

only found on cliff faces in the most inaccessible places," said Ahmed.

The trees take nearly half a

century before they reproduce, he explained. "If nothing is done, it will

not take long before all are gone," he said.

- 'Running out of time' -

The shrinking forests are a canary

in the mine for Socotra's environmental challenges, said Belgian biologist Kay

Van Damme, from the University of Ghent.

"It remains a treasure trove of

biodiversity," said Van Damme, chair of the Friends of Socotra support

group. "But we may soon be running out of time to protect Socotra's most iconic

flagship species."

Each lost tree drives a reduction

in the hydrological cycle on which all life depends.

Islanders say trees have been

battered by storms more ferocious than anyone remembers.

At Diksam, on the high plateau

surrounding the Hagher mountains, running like a spine along the 130-kilometre

(80-mile) island and 1,500 metres (4,900 feet) high, dead trees lie scattered

like bowling ball pins.

Other local species are just as

hard hit by storms and overgrazing, including the 10 endemic species of

frankincense tree.

Gales have torn through nearly a

third of the trees in the Homhil forest over the past decade.

Without replanting efforts, the

forest "will be gone in only a few decades", Van Damme said.

One study found the number of

frankincense trees had plummeted by 78 percent in this area between 1956 and

2017.

"The immune system of Socotra is now

compromised," he said, but added, "there is still hope."

Landslide scars caused by

vegetation loss are now a common sight.

"If the trend continues, future generations

might be able to visit a Socotran frankincense tree only in a botanical garden,

accompanied by a little plaque saying 'extinct in the wild'", Van Damme

added.

The International Union for Conservation

of Nature (IUCN) warns that Socotra is under "high threat", and the

"deteriorating" situation will be "accelerated by climate change".

Islanders are already feeling the

impact of changing weather patterns.

Abdullah Ahmed, from a small fishing

village near Shuab, a cluster of solidly built coral-stone homes, said the 40

residents were threatened both by extreme high seas and landslides.

They have built a new village 10

minutes' walk from the sea.

"Waves in the last storms smashed the windows of

our home," the 25-year-old said, describing how his family had sheltered

terrified in caves for days.

"The last monsoon was worse than anyone had

experienced."

But with effort, the worst impact

can be slowed -- and some Socotris are doing what they can to protect their

island.

Adnan Ahmed peered over the

chest-high stone wall of a community-run dragon's blood tree nursery, a

football-pitch sized area enclosed against goat invasions.

Inside are dozens of knee-high

saplings. Resembling pineapple plants, they are the painstaking result of at

least 15 years' growth.

"It is a start, but much more is needed,"

he said. "We need support."

Sadia Eissa Suliman was born and

raised at the Detwah lagoon, listed as a wetland of global importance under the

Ramsar wetlands convention.

"I saw how the lagoon was changing," said

the 61-year old grandmother, who watched swathes of trees being chopped down,

plastic being dumped and fishing nets trawling the water, a critical nursery

for young fish.

"Everyone said someone else would do

something," she said. "But I said, 'Enough: I will do it, and people

will see the difference.'"

She now helps the community

enforce a fishing ban and raises funds to enclose trees and to tackle littering.

Scientists are also determined

Socotra will not just become another case study of loss.

"We have a chance as humans to not mess this one

up, otherwise we've learnt nothing from other examples of huge extinctions on

islands," Van Damme said.

"Socotra is the only island in the entire world where no reptile, plant or bird that we know of has gone extinct in the last 100 years. We have to make sure it stays that way."