India the frontline in big tech’s assault on democracy

In 10 days’ time, two political dramas will reach

their denouement, thanks to the votes of a combined total of about 1.3 billion

people. At the heart of both will be a mess of questions about democracy in the

online age, and how – or even if – we can act to preserve it.

Elections to the European parliament will begin on

23 May, and offer an illuminating test of the rightwing populism that has swept

across the continent. In the UK, they will mark the decisive arrival of Nigel

Farage’s Brexit party, whose packed rallies are serving notice of a politics

brimming with bile and rage, masterminded by people with plenty of campaigning

nous.

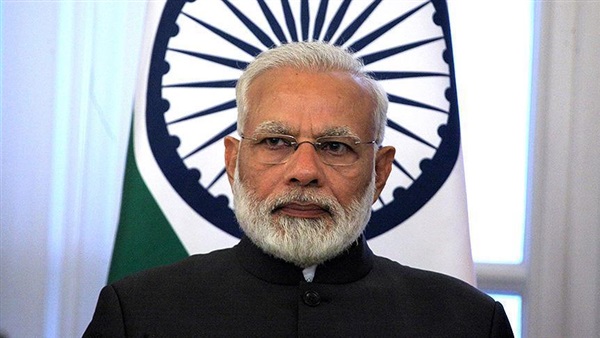

The same day will see the result of the Indian

election, a watershed moment for the ruling Hindu nationalist prime minister,

Narendra Modi, and his Bharatiya Janata party, or BJP.

Whatever the outcomes, both contests will highlight

something inescapable: that the politics of polarisation, anger and what

political cliche calls “fake news” is going to be around for a long time to

come.

In Facebook’s European headquarters in Dublin,

journalists have been shown the alleged wonders of the “war room” where staff are

charged with monitoring European campaigning – in 24 languages – and somehow

minimising hate speech and misinformation put around by “bad actors”.

But this is

as nothing compared with what is afoot in the world’s largest democracy, and a

story centred on WhatsApp, the platform Mark Zuckerberg’s company acquired in

2014 for $22bn, whose messages are end-to-end encrypted and thus beyond the

reach of would-be moderators. WhatsApp is thought to have more than 300 million

Indian users, and though it is central to political campaigning on all sides,

it is Modi and his supporters who have made the most of it.

The political aspects of this blur into incidents of

murder and violence traced to rumours spread via WhatsApp groups – last week,

the Financial Times quoted one Indian political source claiming that WhatsApp

was “the echo chamber of all unmitigated lies, fakes and crap in India”.

When I spoke to the UK-based Indian academic

Indrajit Roy last week he acknowledged India’s “dangerous discourse” but

emphasised how the online world had given a voice to people who were once

outsiders.

He talked

about small, regional parties live-streaming rallies in “remote parts of north

India”; memes that satirised “how idiotic and self-obsessed [Modi] is”; and

people using the internet to loudly ask why India’s caste hierarchies held them

back so much.

But then came the flipside. In that context, he

said, it was perhaps not surprising that Modi was now leading “an elite revolt

against the kind of advances that have happened in the past five or six

decades, whether it’s the rights of minorities, so-called lower castes, or

women”. The fact that he and the BJP are using the most modern means of

communication to do so is an irony evident in the rise of conservatives and

nationalists just about everywhere.

This, then, is an Indian story, but it chimes with

what is happening all over the planet. With the help of as many as 900,000

WhatsApp activists, the BJP has reportedly collected reams of detailed data

about individual voters and used it to precisely target messages through

innumerable WhatsApp groups. A huge and belligerent online community known as

the Internet Hindus maintains a shrill conversation about the things that its

members think are standing in the way of their utopia: Muslims, “libtards”,

secularists.

There are highly charged online arguments about

Indian history, often led by the kind of propagandists who never stand for

office and thus put themselves beyond any accountability.

Thanks to the Indian equivalent of birtherism, there

are also claims that the Nehru-Gandhi family, who still dominate the opposition

Congress party, have been secret followers of Islam, a claim made with the aid

of fake family trees and doctored photographs.

Partly because forwarded messages contain no

information about their original source, it is by no means clear where the

division between formal party messaging and unauthorised material lies, so Modi

and his people have complete deniability. They benefit, moreover, from the way

that the online world seems to ensure that everything is ramped up and divided.

To quote

Subir Sinha, an Indian analyst of society and politics based at London’s School

of African and Oriental Studies: ”You can’t just be a nationalist; you’ve got

to be an ultra-nationalist. You can’t just be upset by Pakistan’s actions;

you’ve got to be outraged.”

He calls this “hyper-politics”, and says that its

international lines of communication have led some to some remarkable things.

“Tommy Robinson is extremely popular among Modi supporters,” he told me. “You

will find mega-influencers of the Indian right who will approvingly post Tommy

Robinson material in WhatsApp groups, or on Twitter.”

Yes, the internet is still replete with

possibilities of emancipation and pluralism, but herein lie the basic features

of the global 21st century: disagreements that have always been there in

politics, both democratic and otherwise, now seem to have been rendered

unstoppable by technology.

Significant parts of society are kept in a constant

state of tension and polarisation, a state exacerbated by the algorithms that

privilege outrage over nuance, and platforms that threaten to be ungovernable.

Though the

old-fashioned media maintains the pretence that electioneering is the preserve

of parties, campaigns around elections (and referendums) are actually loose and

open-ended – often mired in hate and division and full of allegations of

corruption and betrayal.

We are seeing the constant hardening-up of political

tribes – religious communities, liberals, conservatives, nationalists,

socialists, cults built around supposedly charismatic leaders – with victory

going to the forces that can most successfully manipulate the online ferment.

Modi is a dab hand at this. So are the forces behind

the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro. Important Brexiteers are expert in the

same techniques; as evidenced by his Twitter presidency, the same is true of

Donald Trump.

On the left, too, there are clear manifestations of

a politics transformed by the way we now communicate – not least in and around

Corbynism, which represents both sides of the new reality: simultaneously the

most serious threat to established thinking for decades and a long-overdue push

against inequality and the lunacies of the free market, and also the focus of a

shrill, all-or-nothing, sometimes truth-bending online discourse.

Whether the platforms at the heart of this new world

might eventually start to get to grips with the downsides of what they have

created is a question obscured at present by unconvincing half-measures, and

the kind of flimsy PR embodied by a recent WhatsApp advertising campaign that

encouraged its users in India to “Share joy, not rumours”.

The reality of where we are headed was perhaps

highlighted only a few months ago, when Zuckerberg announced a new vision for

Facebook, built around the mantra “The future is private”, and a proposal to

make his most successful invention much more like WhatsApp – an attempt, as

some people saw it, to start a journey towards Facebook having no

responsibility for the content of its networks because encryption would render

everything conveniently impenetrable.

In that sense, the Indian experience may not be any

kind of outlier but a pointer to all our futures. If that turns out to be true,

what are we going to do about it?