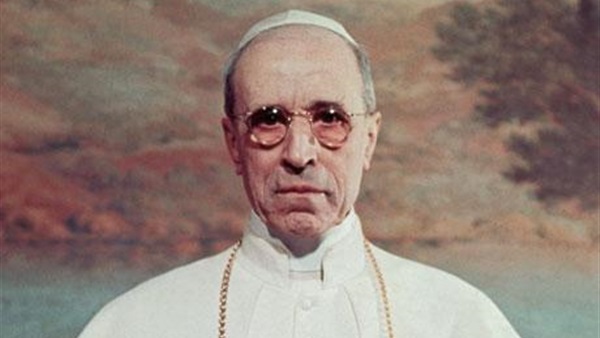

Unsealing of Vatican archives will finally reveal truth about ‘Hitler’s pope’

New light will be shed on one of the most

controversial periods of Vatican history on Monday when the archives on Pope

Pius XII – accused by critics of being a Nazi sympathiser – are unsealed.

A year after Pope Francis announced the move, saying

“the church isn’t afraid of history”, the documents from Pius XII’s papacy,

which began in 1939 on the brink of the second world war and ended in 1958,

will be opened, initially to a small number of scholars.

Critics of Pius XII have accused him of remaining

silent during the Holocaust, never publicly condemning the persecution and

genocide of Jews and others. His defenders say that he quietly encouraged

convents and other Catholic institutions to hide thousands of Jews, and that

public criticism of the Nazis would have risked the lives of priests and nuns.

“The opening

of the archives is decisive for the contemporary history of the church and the

world,” said Cardinal José Tolentino Calaça de Mendonça, the Vatican’s

archivist and librarian last week.

Bishop Sergio Pagano, the prefect of the Vatican

Apostolic Archive, said scholars would have to make a “historical judgment”. He

added: “The good [that Pius did] was so great that it will dwarf the few

shadows.” Evaluating the millions of pages in the archives would take several

years, he said.

More than 150 people have applied to access the

archives, although only 60 can be accommodated in the offices at one time. Among

the first to view the documents will be representatives of the Jewish community

in Rome, and scholars from Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum, and the

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

David Kertzer, an American expert on the

relationship between the Catholic church and fascism, who will begin examining

the papers this week, said there were “signs of nervousness” at the Vatican

about what would emerge from the archives. The Vatican archives would provide

an “immense amount of fresh material from many millions of pages”, he told the

Observer.

“On the big question, it’s clear: Pius XII never

publicly criticised the Nazis for the mass murder they were committing of the

Jews of Europe – and he knew from the very beginning that mass murder was taking

place. Various clerics and others were pressing him to speak out, and he

declined to do so.

“Although there is a lot of testimony showing that

the church did protect Jews in Rome, when more than 1,000 were rounded up on 16

October 1943 and held for two days adjacent to the Vatican [before deportation

to the death camps], Pius decided not to publicly protest or even privately

send a plea to Hitler not to send them to their deaths in Auschwitz. Hopefully,

what we’ll find from these archives is why he did what he did, and what

discussions were going on behind the walls of the Vatican.”

Mary Vincent, professor of modern European history

at Sheffield University, said that much of the criticism of Pius Xll lacked

nuance. “He was a careful, austere and quite unlikable man, trying to steer a

path through almost impossible circumstances. He had clear views about what he

saw as the threat of Soviet communism, and his view of Italian fascism was

quite a bit softer. But categorising him as good or bad is not helpful – it’s

about the decisions he took, and the space he had to make those decisions.”

Pius – whose birth name was Eugenio Pacelli – was

Vatican secretary of state under his predecessor, Pope Pius XI, and a former

papal nuncio, or envoy, to Germany. In 1933, he negotiated a concordat between

the Catholic church and Germany. After he was elected pope, six months before

the outbreak of war, the Vatican maintained diplomatic relations with the Third

Reich, and the new pontiff declined to condemn the Nazi invasion of Poland on 1

September 1939.

In December 1942, Pius XII spoke out in general

terms about the suffering of the Jews, although he had known for several months

about the Nazi extermination plans. In 1943, he wrote to the bishop of Berlin,

arguing that the church could not publicly condemn the Holocaust for fear of

causing “greater evils”.

Hitler’s Pope, a controversial biography of Pius XII

by British author John Cornwell, published in 1999, claimed the pope was an

antisemite who “failed to be gripped with moral outrage by the plight of the

Jews”. He was also narcissistic and determined to protect and advance the power

of the papacy, the book argued. Pius XII was “the ideal pope for Hitler’s

unspeakable plan. He was Hitler’s pawn. He was Hitler’s Pope.”

Cornwell’s claims were challenged by some scholars

and authors. He later conceded that Pius XII had “so little scope of action

that it is impossible to judge the motives for his silence during the war”,

although the pontiff had never explained his stance.

In 2012, Yad Vashem changed the wording on an

exhibit on Pius XII’s papacy, from he “did not intervene” to he “did not

publicly protest”. The new text acknowledged different assessments of the

pope’s position and Yad Vashem said it “look[ed] forward to the day when the

Vatican archives will be open to researchers so that a clearer understanding of

the events can be arrived at”.

Pope Benedict, Francis’s predecessor, declared in

2009 that Pius XII had lived a life of “heroic” Christian virtue, a step

towards possible sainthood. But in 2014, Francis said no miracle – a

prerequisite for beatification, the final step to canonisation – had been

identified. “If there are no miracles, it can’t go forward. It’s blocked

there,” Francis said after visiting Yad Vashem. Last year, Francis said Pius

XII had led the church during one of the “saddest and darkest periods of the

20th century”. He added that he was confident that “serious and objective

historical research will allow the evaluation [of Pius] in the correct light,”

including “appropriate criticism”.