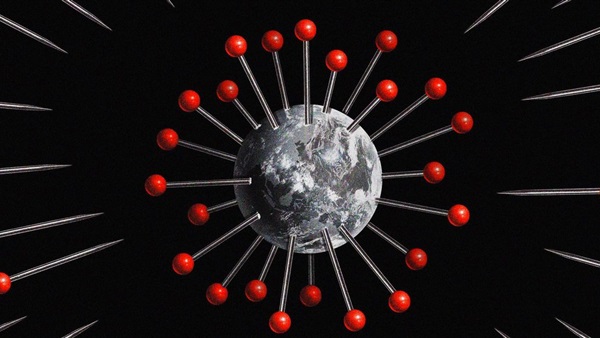

Coronavirus crisis could double number of people suffering acute hunger – UN

The coronavirus crisis will push more than a quarter

of a billion people to the brink of starvation unless swift action is taken to

provide food and humanitarian relief to the most at-risk regions, the UN and

other experts have warned.

About 265 million people around the world are

forecast to be facing acute food insecurity by the end of this year, a doubling

of the 130 million estimated to suffer severe food shortages last year.

“Covid-19 is potentially catastrophic for millions

who are already hanging by a thread,” said Dr Arif Husain, chief economist at

the World Food Programme.

“It is a hammer blow for millions more who can only

eat if they earn a wage. Lockdowns and global economic recession have already

decimated their nest eggs. It only takes one more shock – like Covid-19 – to

push them over the edge. We must collectively act now to mitigate the impact of

this global catastrophe.”

Global hunger could become the next big impact of

the pandemic, warns the Global Report on Food Crises, by the UN Food and

Agriculture Organisation, the World Food Programme and 14 other organisations,

published on Tuesday. Some of the poorest countries may face the choice of

trying to save people stricken by the virus only for them to fall prey to hunger.

António Guterres, the UN secretary-general, said the

report must be a call to action.

“The upheaval

that has been set in motion by the Covid-19 pandemic may push even more families

and communities into deeper distress,” he wrote in the foreword.

“At this time of immense global challenges, from

conflicts to climate shocks to economic instability, we must redouble our

efforts to defeat hunger and malnutrition. We have the tools and the knowhow.

What we need is political will and sustained commitment by leaders and

nations.”

The report, which will be presented to the UN

security council on Tuesday afternoon, bolsters warnings that the world could

face a repeat of the 2007-08 food price rises that sparked widespread political

upheaval, the impacts of which are still being felt across the Middle East and

from Asia to Latin America.

Food experts are worried that donor nations have

barely begun to deliver the funding needed urgently on the ground to set up

networks to deliver humanitarian relief to the worst-hit areas, deliveries

which need to be achieved by air as ground transport is obstructed or halted

over large areas.

The World Food Programme estimates that $350m

(£280m) will be needed immediately, but only about a quarter of the sum has yet

been forthcoming.

The pandemic was first felt in some of the world’s

biggest economies, originating in China, then hitting Italy and Spain, and now

the US has become the centre. There is less data available on the spread in

developing countries, where widespread testing is not being done and healthcare

systems are often lacking.

The report finds that already stretched health

services in developing countries are likely to be overwhelmed, while a global

recession will disrupt food supply chains. There are particular concerns for

people working in the informal economy, and the world’s 79 million refugees and

displaced people.

Labour shortages as people fall ill may put further

strain on food production, protectionist measures may increase food prices, and

rising unemployment will reduce people’s purchasing power, driving more into

hunger.

On the plus side, harvest prospects for staple crops

are good, but the movement restrictions to contain the spread of the virus will

create problems for food distribution.

Poorer countries are bracing for the full impact of

Covid-19 on their health systems, and are already seeing the effects of the

economic shutdown that has sent the world spiralling into recession.

Some of the poorest nations “may face an

excruciating trade-off between saving lives or livelihoods or, in a worst-case

scenario, saving people from the coronavirus to have them die from hunger”, the

report warned.

Even without the impact of coronavirus, the outlook

for many countries – such as Yemen, where conflict has led to millions facing

starvation, and in east Africa, where locusts are posing a famine threat – was

already dire.

Despite good recent harvests in many parts of the

world, the extra stress of the pandemic will take many other nations riven by

conflict or political unrest beyond breaking point. Extreme weather driven by

climate breakdown is also likely to add to the toll, as it did last year.

Last year, of the 130 million people suffering acute

food insecurity, the majority (77 million) were in countries afflicted by

conflict, 34 million were hit by the climate crisis, and 24 million were in

areas where there was an economic crisis.

Charities and civil society groups are also calling

on rich countries’ governments to take action to help the poorest at risk of

starvation.

Catholic Relief Services in the US is campaigning

for the US Congress to devote new funds to the fight urgently.

“The pandemic is a crisis on top of a crisis in

parts of Africa, Latin America and Asia,” said Sean Callahan, chief executive

of the charity.

“The severe health risks are only part of the

outbreak. Lockdowns are hampering people from planting and harvesting crops, working

as day labourers and selling products, among other problems. That means less

income for desperately hungry people to buy food and less food available, at

higher prices.”

Multinational food companies also recently warned

that the number of people in chronic hunger could double to more than 1.6

billion as a result of the pandemic, and urged world leaders to take action.

Nobel prize-winning economists have warned that developed nations will increase

the threat of damaging recurrences of the virus in their own countries if they

fail to fund measures in the poor world.

However, there are signs that international

cooperation on the pandemic is under strain. The US refused to sign up to an

extensive draft communique by G20 health ministers that bolstered the role of

the World Health Organization, preferring a brief version that acknowledged

gaps in the world’s preparedness, and president Donald Trump has halted US

funding for the WHO.