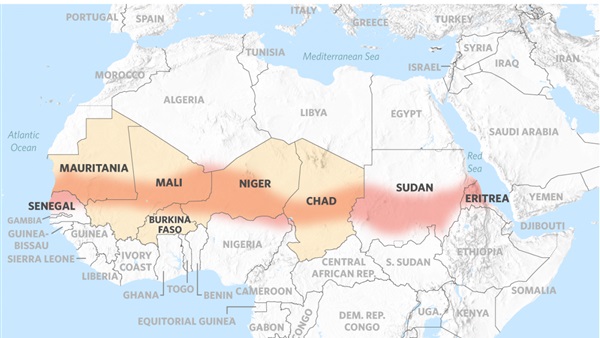

The Black Corridor: The New Map of Terror in the African Sahel

The Sahel region of Africa is no longer a geographical

margin on the map of the continent—it has become the very heart of the security

equation in Africa and the world.

From Mali to Burkina Faso and on to Niger stretches the

“belt of fire” that Western analyses now call “the Black Corridor”—the dark

strip that is redrawing the borders of terrorism and international influence on

the continent.

Within less than a decade, these three countries have

shifted from being Western partners in counterterrorism to open arenas for

extremist groups, foremost among them Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its

strongest arm in the region: Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

This transformation did not occur overnight. It resulted

from a chain of coups, shifting power policies, international withdrawals, and

internal divisions that left a political and security vacuum—one swiftly filled

by armed organizations.

When French and UN forces retreated from Mali, extremist

groups rushed to fill the gap, as the central state appeared unable to assert

its authority and national armies were exhausted by endless wars with no clear

end.

Today, the map of the Sahel is being redrawn—from

northern Mali to the borders of Burkina Faso and Niger—where the contours of a

“cross-border emirate of terror” are forming before the world’s eyes, led by

JNIM, Al-Qaeda’s most powerful branch in Africa.

According to Le Monde, the withdrawal of international

forces from Mali “unleashed an unprecedented wave of attacks,” while BBC Africa

reports that armed groups now move across the tri-border areas with unmatched

freedom, exploiting weak state presence, vast desert expanses, and the collapse

of local intelligence systems.

The Washington Post describes the situation as “a silent

slide into the abyss,” warning that what was once the “protective belt” of West

Africa has now become its “soft underbelly” before the advance of terrorism.

On the ground, black flags alternate in control over

entire regions—sometimes under Al-Qaeda through JNIM, sometimes under the

“Islamic State in the Greater Sahara,” alongside local militias loyal to

whoever pays or supplies weapons.

Reports by Africa Intelligence and Crisis Group indicate

that the number of terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso alone has increased more

than fivefold in three years, while the central government has lost control of

about 45% of its territory, mostly in the north and east.

From Mali: The Beginning

In the heart of the Sahara, the first spark was lit.

Since jihadist groups seized northern Mali in 2012, the

country has suffered chronic fragmentation despite repeated international

interventions.

The fall of Mali was not sudden—it crowned years of

political and military exhaustion.

A state once seen, until 2012, as one of West Africa’s

most stable regimes, became within a decade an open theater for proxy wars,

with UN troops, Russian mercenaries, and local jihadists alternating control in

a highly complex mix.

Le Monde notes that the decisive turning point came with

the mid-2024 withdrawal of the UN’s MINUSMA mission, when Malian army positions

in the north collapsed within weeks, leaving major cities in the hands of JNIM,

which filled the void with astonishing speed.

According to Africa Intelligence, the group seized key

routes between Gao, Ménaka, and Timbuktu, imposed “transit taxes” on locals,

and established Sharia courts to settle disputes—a scene reminiscent of the

Taliban’s rule in Kabul before its first fall.

JNIM swiftly occupied strategic cities such as Gao,

Ménaka, and Timbuktu, setting up checkpoints and tax centers and enforcing what

it calls “Sharia,” in an almost full replication of the Taliban model in

Afghanistan—but with African features.

The Malian army, drained by years of fighting, retreated

to the vicinity of the capital Bamako, while JNIM expanded north, center, and

east.

Reports by Crisis Group and The Economist indicate that

more than 60% of Mali’s territory is now outside government control.

The French military operation Barkhane, launched in 2014,

failed to eliminate terrorism and ended with Paris’s withdrawal in 2023 under

public pressure and rising anti-Western sentiment.

That withdrawal marked a decisive shift: Russian Wagner

forces replaced the French but soon found themselves in limited engagements

that changed nothing in the state of collapse.

According to Reuters, 2024 alone saw more than 2,500

terrorist attacks in Mali—mainly in Mopti, Gao, and Timbuktu. ACLED data

confirm that these groups do more than fight: they govern civilians, collect

taxes, and control trade and gold routes.

In Bamako, the government of Colonel Assimi Goïta

promotes a narrative of “liberation from colonialism,” yet it faces an

undeniable reality:

The state is crumbling at the edges, and tribal and

ethnic loyalties have replaced national allegiance.

Reuters notes that the Malian army now depends almost

entirely on Wagner for protection of the regime rather than actual combat,

while jihadists make tangible advances, recruiting thousands of unemployed

youths under slogans of “justice and equality.”

Crisis Group reports that these groups operate not only

with religious ideology but with pragmatic governance, forging deals with

village chiefs and traders, imposing “taxes for protection,” and presenting

themselves as substitutes for an absent state.

According to The Conversation Africa, the group has

succeeded in “turning popular anger over corruption and discrimination into

armed ideological loyalty”—a far more dangerous evolution.

During the latter half of 2024, JNIM fighters crossed

into Burkina Faso and Niger, welcomed by pre-established sleeper cells.

BBC Africa describes this as a “soft transfer of

influence,” achieved not by invasions but by gradual infiltration and purchase

of local loyalties—creating a regional network that functions without a single

command center.

By late 2024, Mali had ceased to be merely a failed

state; it became the prototype of a new jihadist governance model—more

structured and less chaotic than before.

The Washington Post warns that “the group has learned

from ISIS’s mistakes in Iraq and Syria, now preferring incremental control to

open confrontation with the international community.”

Analysts cited by Africa Report now speak of a “post-Mali

map” stretching from northern Burkina Faso to Tillabéri in Niger—where Al-Qaeda

and ISIS’s most dangerous cells operate across an area larger than France.

With Western forces withdrawing in succession, observers

predict that within two years the Sahel could transform into an African version

of the “Jihadist Crescent” that once stretched from Afghanistan through Syria

and Iraq.

Burkina Faso: From Capital to Burning Peripheries

In Burkina Faso’s southwest, tragedy repeats itself in

more complex form.

Since the 2022 coup, the security system has collapsed

and armed groups have expanded deep into the country at an unprecedented pace.

Le Monde Afrique calls this “the slow collapse of an

entire state before the eyes of the world.”

BBC Africa reports that terrorist attacks have multiplied

fivefold in just three years, making Burkina Faso the bloodiest hotspot in the

Sahel.

Crisis Group estimates that nearly 45% of its land is

outside central control, with armed groups dominating the north, east, and west

and using border zones with Mali and Niger as main operational bases.

Le Monde describes the situation as “a slow-motion

disintegration,” with the capital surrounded on three sides and dozens of

villages cut off from all supply and communication routes.

Reuters reports that the number of internally displaced

persons has exceeded 2.3 million—among the world’s highest.

JNIM follows a “gradual infiltration” strategy—building

presence in villages and tribal communities by providing substitutes for state

services: security, customary justice, food aid—in exchange for loyalty and

obedience.

ISIS in the Greater Sahara, concentrated in the east,

seeks to control vital routes with Niger and Mali. The two groups, while

competing for influence and resources, share the goal of toppling the state and

establishing a “Greater Sahel Emirate.”

Africa Intelligence notes that since late 2024, the two

organizations have informally divided zones of influence to avoid internal

conflict and focus on fighting the Burkinabe army.

In response, the government of Captain Ibrahim Traoré has

rallied under the slogan of “popular resistance,” recruiting over 50,000 armed

volunteers known as “Homeland Defense Forces.”

Yet Reuters observes that most lack training and adequate

arms, becoming easy targets—and some later joined jihadist groups after being

abandoned without pay or support.

The Economist warns that Burkina Faso’s total collapse

would open a gateway for terrorism to spread into West Africa’s coastal

states—Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, and Benin—marking the first expansion from

desert to rainforest.

Niger: On the Brink of Collapse

If Mali has fallen and Burkina Faso is collapsing, Niger

now stands on the edge.

Of the three burning states, Niger is the most

geopolitically sensitive—both the Sahel’s gateway to North Africa and its last

defensive line against jihadist reach to the Mediterranean.

Since the July 2023 coup, the impoverished nation has

faced a political and security vacuum drawing fire from all directions.

The Economist notes that Niger had been the West’s last

effective ally in the Sahel until President Mohamed Bazoum was deposed,

ushering in isolation and exposure.

With French forces expelled and intelligence cooperation

with the U.S. suspended, Russian influence—via Wagner’s rebranded “Africa

Corps”—entered gradually under the banner of “supporting security and

stability,” while armed groups expanded freely.

The Washington Post states that “a coup born in the name

of security has birthed greater chaos.”

Reuters adds that the political vacuum in Niamey has

become fertile ground for terrorist expansion, especially after Western

withdrawals, making the tri-border zone the continent’s most dangerous.

Crisis Group reports that JNIM and ISIS-Sahel rapidly

extended control over Tillabéri, Tahoua, and Ménaka, while Boko Haram increased

attacks along the Chadian border.

Reuters (September 2025) notes a 70% rise in attacks

within one year, killing over 1,200 people—soldiers and civilians alike.

Internally displaced persons now number roughly 750,000,

mostly from the western regions plagued by ISIS activity.

Le Monde Afrique describes Niger’s situation as “erosion

of the state from the peripheries toward the center,” warning that continuing

ethnic divisions between Tuareg and Fulani could bring total collapse within

two years unless political balance is restored.

The Black Corridor: From Chaos to Repositioning

The vacuum left by French withdrawal has not yet been

filled by Russia—but by terrorist groups themselves.

The border zone between Tillabéri and Ménaka now serves

as a free corridor between Mali and Niger, while fighters from Burkina Faso

have moved southwest into Niger.

BBC Monitoring confirms that armed groups use this area

as a “secure triangle” for exchanging weapons, fighters, and funds.

ACLED data show that over 60% of Sahel attacks in 2025

occurred within the narrow strip linking Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso—an area

barely 15% of the region’s total size.

Western media now call it the “Black Corridor”—the

expected epicenter of Africa’s next conflict.

Stretching from northeastern Mali through western Burkina

Faso to southwestern Niger, it is the most dangerous terrorist corridor on

Earth today.

According to International Crisis Group (October 2025),

this corridor has evolved from a zone of insecurity into an alternative

governance system imposed by JNIM and ISIS-Sahel.

In remote villages, these groups now dispense “local

justice,” collect taxes, regulate markets, and prevent livestock theft in

exchange for allegiance—replicating northern Mali’s 2012 model before the

declaration of “Azawad Emirate.”

Le Monde Afrique notes: “The Sahel’s militants are no

longer mere rebels; they have become de facto authorities governing daily life

across vast territories, functioning as a full shadow state.”

The Guardian calls this shift “the management of chaos,”

whereby these groups evolve from assailants to administrators.

ACLED estimates that over 40% of border-zone residents in

Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger now live entirely outside central government

control.

Both The Guardian and Crisis Group analyses converge on

one conclusion: JNIM has built a “shadow governance network” managing

resources, markets, taxation, and courts—making it more than an armed movement;

it is a parallel state gaining strength with every official withdrawal.

Reuters estimates annual revenues from gold trade alone

exceed $150 million, funding arms purchases and recruitment.

The Washington Post notes that Al-Qaeda and ISIS have

redistributed roles to avoid direct confrontation: Al-Qaeda dominates populated

areas while ISIS controls desert routes.

Africa Intelligence concludes this is not merely

terrorist expansion but a “global repositioning of Al-Qaeda and ISIS in the

heart of Africa” after their Middle Eastern decline.

With its geography bridging the Mediterranean and the

continental interior, its wealth of resources, and weak governments, the “Black

Corridor” is becoming a strategic launchpad for a new, decentralized

“caliphate.”

The Economist Intelligence Unit warns that total collapse

of Burkina Faso or Niger would transform the Sahel into an “African

Afghanistan,” threatening both North and West Africa while opening space for

Russian, Iranian, and Israeli influence amid Western retreat.

As repeatedly warned in the Other Bank program on Cairo

News Channel, the French withdrawal from the Sahel signaled the start of

successive collapses unless regional powers act urgently.

What happened in Mali was not just political failure—it

proved that institutional vacuums breed armed, organized, and enduring

alternatives.

Niger and Burkina Faso now stand at a historic

crossroads:

either mass local and regional mobilization to restore

control—or surrendering the arena to emerging “parallel powers” with greater

endurance and influence.

Hence, the documentation, analysis, and warning efforts

by media outlets such as ours—and by The Other Bank program—are not a luxury

but a regional duty, raising alarms that must be heeded now.

After reviewing all analyses, the conclusion is clear:

The total collapse of Niger would open the road for

terrorist groups toward Algeria and Libya in the north, Nigeria in the west,

and Chad in the east—toward the very heart of the continent.

It would also undermine any future Western presence in

the region and grant Russia, Iran, and Israel open influence in a zone no

longer governed by global balance.

As The Other Bank has often emphasized: what is unfolding

in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali is not mere domestic upheaval but a redrawing

of Africa’s power map—through terrorism instead of armies.

The Sahel’s militant groups now move freely across three

countries, empowered by arms, gold, and fuel smuggling networks.

The international community fails to grasp that these

groups no longer need a declared capital—they have turned the entire map into

an open field for a silent, de facto caliphate.

Who Is Next to Fall?

Based on current indicators—JNIM’s tactics, Niger’s

border weakness, Burkina Faso’s economic fragility, and Mali’s

precedent—Burkina Faso and Niger are effectively competing for the title of

“next state to collapse.”

Yet the indicators point more strongly to Niger.

Forecast summary:

Short-term (1–3 years): Niger — structural

vulnerabilities (open borders, declining foreign partners, inward-focused

regime survival) make it the likeliest candidate for broad militant dominance.

Medium-term (3–5 years): Burkina Faso — gradual

“functional fragmentation” and erosion of central authority will replicate

Mali-like enclaves without an immediate national collapse.

This does not imply an instant fall of capitals, but a

progressive division of governance between armed actors and weakened state

institutions.

Thus the new African tragedy is summed up in one

equation:

Weak states, strong groups, and an international silence

watching from afar, as the Sahara becomes a laboratory for reinventing

terrorism in a new form.

Prepared and analyzed by: Dalia Abdel Rahim

Editor-in-Chief, Al-Bawaba News