A Morning Like a Promise

A day like a promise.

Tomorrow, a new day will rise,

and a new year;

children slip their hands into

their mothers’ hands without resistance,

and the shuttle begins its motion

in the poultry yards.

Church bells ring out with joy,

and mosques resound with the call

of a new dawn…

A feast day, and an ordinary one…

yet it is a morning that

resembles a promise.

So the evening soothsayer told

me,

and whispered to me in silence:

Raise your voice with song… songs

are still possible,

and even if one day you break,

you must rise standing,

like the palm trees gazing at the

sky…

No defeat… no fracture… no fear…

no… no dream sprouting in the wilderness…

This meaning has enveloped my

life, and still does. Many battles I have fought under this banner, weaving

through it my own legend: no breaking, no defeat.

The dream is planted in the open

land, watered by the Nile;

the soil is black silt, and the

crops are vigorous.

Pitchers of honey, and varieties

of the soul’s delicacies,

we laid them beside what we

planted in the expanse;

and the horizon yielded dreams

and tales

that drifted along the banks of

the soul

and wrapped the heart in a

permitted love…

I, the undersigned, hereby

confess that I am utterly and of my own free will entangled in that tale, that

beautiful predicament that has possessed me for forty years or more, since I

was twenty.

Of forty years of honey I write; of

the windows of our lives that we opened early onto Munir and Abdel Rahim

Mansour, so our visions widened, we touched the dream, and wonder filled us, as

if we were being born from the very first touch…

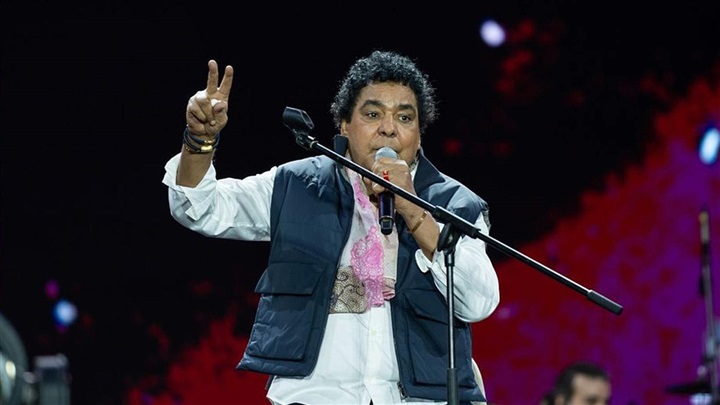

Of an innocent one, brown like

chocolate, who came from the warm Nubia of Egypt and burst into our lives with

steadiness, confidence, and singularity.

He was the very opposite of his

era; so some denied him,

some marveled at him, and some

feared him— those who had grown addicted to the familiar and the prevailing, who

lulled themselves with dull romanticism, with melodies of vocal ornamentation, the

vocabulary of worn-out dictionaries, pre-fabricated meanings of words, and

recycled tunes.

The brown boy, chocolate-colored,

emerged,

disheveled in hair and in soul,

panting with jealousy for his

country—

simple, from the heart of the

circle,

as if entrusted with the space of

the soul to cultivate it,

to arrange nature,

to tailor feelings and emotions.

He invited us—

not only to listen to him with

our hearts and our consciousness,

but, in the footsteps of the

great master Sayed Darwish,

to allow us to sing with him.

He sang to us, and we sang with

him;

he taught us a beautiful, sly

trick—

we lovers, seized by shyness,

lacking the courage to confess

our feelings to our beloveds—

back then, we would whisper, or

repeat in their ears,

snippets of his songs:

They taught me, from your eyes,

how to travel…

O bride of the Nile, a piece of

the sky…

You whose image inside my heart

is an epic…

He blended the beloved with the

homeland,

and the homeland with the

beloved,

until eyes and hearts became one.

If the arrow struck the beloved’s

heart—

all well and good.

And if not,

we would dodge and say:

we meant the homeland.

The words of Abdel Rahim Mansour,

and the voice and sensibility of

Mohamed Mounir,

granted us comfort, depth, and

intimacy.

Munir’s songs,

and the poems of Ahmed Abdel

Moaty Hegazy,

Mahmoud Darwish, and Salah Ghahin,

formed the vocabulary of our

first love letters,

and our lovely ruses for

communicating with our beloveds

in our twenties.

Munir called on us to write our

names

in the ledger of the homeland,

to speak, to confess:

Why do you keep silent before

time… speak.

Why do you pay the price alone…

speak.

And when treachery and terrorism

struck

the heart of the homeland,

Munir sang: The heart of the

homeland is wounded.

And when deceitful thieves,

merchants of religion,

tried to steal Egypt,

to strip its history, culture,

and arts,

and to forbid joy to Egyptians,

there was Munir’s icon and his

immortal cry:

Madad, madad, madad,

Madad, O Messenger of God.

I swear by the Furqan,

and by Surat Al-Insan,

justice is in the balance,

for all of God’s creation.

Madad, madad, madad,

Madad, O Messenger of God.

I swear by Al-Isra,

and by the innocence of the

Virgin,

all blood is equal,

sacred by the command of God.

Munir sang, and thus forged a

manifesto

for revolution against injustice

in every place and every time:

How can you accept this for me,

my beloved—

that I am passionately in love

with your name while you

keep adding to my confusion,

unaware of my kindness—how?

How can you leave me in my

weakness?

Why are you not standing on my

side?

I lived my whole life as it is

so I would never see fear in your

eyes.

I find no motive in your love,

nor does my sincerity plead my

case in your affection.

How can I hold my head high for

you,

while you bend down upon my head—

how?

If I were in love with you by

choice,

my heart would have changed long

ago,

and your life I would have

changed for the better,

for you, until you were satisfied

with it.

He took the side of the simple

people—

the poor farmers,

the kind-hearted workers.

He sang for the stranger and his

heroism,

for the soldiers,

for the girl in the navy-blue

pinafore,

for the cross,

for the crescent,

for Jerusalem,

for the intifada,

for the martyrs,

for life.

He rediscovered the treasures of

musical heritage,

not only in Egypt,

but across the Arab world—

from Algeria and Morocco

to Tunisia and Libya,

and from Sudan

to Lebanon, Jordan, and

Palestine.

Munir has the right to take pride

in what he has given us;

and we have the right—and the

duty— to take pride in him, and to declare our allegiance and our love for him.

Here I write my confession as a

recipient— a lover— entangled in Munir’s musical world.

He opened a new year with his

words, with optimism and confidence in the future.

I am not a critic, but I am

biased—yes.

I say what I see,

what I feel,

what is mine in this tale.

And I know, at the same time,

that millions share with me this

love, this allegiance,

and this gratitude to Munir,

and also share with me optimism

and confidence

in the future and in our day—

the day that is still running and

striving,

still letting its eyes travel,

still whose heart has not grown

weary of the journeys.

Paris: five o’clock in the

evening, Cairo time.