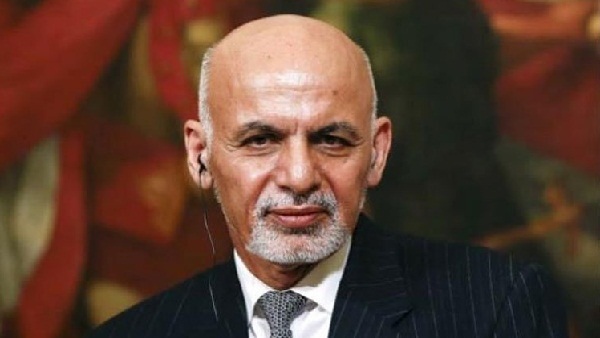

Afghan president names council for peace deal with Taliban

Afghanistan’s president has appointed a council for

national reconciliation, which will have final say on whether the government

will sign a peace deal with the Taliban after what are expected to be

protracted and uncertain negotiations with the insurgents.

The negotiations were envisaged under a U.S.-Taliban

peace agreement signed in February as intra-Afghan talks to decide the war-torn

country’s future. However, their start has been hampered by a series of delays

that have frustrated Washington. Some had expected the negotiations to begin

earlier this month.

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani issued a decree late

Saturday establishing the 46-member council, led by his former rival in last

year’s presidential election, Abdullah Abdullah, who is now in the government.

The council is separate from a 21-member negotiating

team, which Ghani appointed in March and which is expected to travel to the

Gulf Arab state of Qatar, where the Taliban maintain a political office, for

intra-Afghan talks.

The council will have the final say and will

ultimately decide on the points that the negotiating team takes up with the

Taliban.

Abdullah’s appointment to head the reconciliation

efforts followed a power-sharing deal he signed in May with Ghani to end the

political deadlock after last year’s election — a vote in which Abdullah had

also declared himself a winner.

The High Council for National Reconciliation is made

up of an array of Afghan political figures, including current and former

officials, and nine women representatives, one of whom was named Abdullah’s

deputy. Ghani also appointed former President Hamid Karzai to the council but

his predecessor rejected the appointment in a statement Sunday, saying he

declines to be part of any government structure.

Also on the council are mujahedeen and jihadi

leaders who fought against the Soviet Union in the 1980s but who were also

involved in a Afghanistan’s brutal civil war that followed their takeover in

1992 that left 50,000, mostly civilians, dead in Kabul. Among them is Gulbuddin

Hekmatyar, who signed a peace deal with Ghani in 2016 but previously was

declared a terrorist by the U.S.

The council also includes Abdur Rasool Sayyaf, who

was the inspiration for the Philippine terrorist group Abu Sayyaf. During the

1992-1996 civil war, Sayyaf’s fighters killed thousands of minority Shiite

Muslims led by a rival warlord.

However, the establishment of the council may not

sit well with the Taliban, who have appointed just one 20-member negotiating

team that has the authority to make final decisions. The Taliban team answers

only to the insurgents’ leader, Mullah Hibatullah Akhunzada.

There are also other obstacles in the way of the

negotiations. The Afghan government has reversed a decision to release the last

320 Taliban prisoners it is holding until the insurgents free more captured

soldiers.

The U.S.-Taliban deal called on the Taliban to free

1,000 government and military personnel they hold captive while the government

was to free 5,000 Taliban prisoners, in an exchange meant as a goodwill gesture

ahead of the intra-Afghan negotiations.

The government appears adamant to secure freedom for

the soldiers. Javid Faisal, spokesman for the National Security Advisor’s

office, tweeted there are no changes to the plan.

“The Taliban will have to release our commandos held

by them before the government resumes the release of the remaining 320 Taliban

prisoners,” he said.

The U.S.-Taliban deal is aimed at ending America’s

war in Afghanistan — a conflict that began shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks

and toppled the Taliban regime, which had harbored al-Qaida leader Osama bin

Laden.

U.S. troops have already started leaving

Afghanistan, and by November, fewer than 5,000 troops are expected to still be

in the country. That’s down from nearly 13,000 when the U.S.-Taliban agreement

was signed Feb. 29.

Under the agreement, the withdrawal of U.S. troops

does not hinge on the success of intra-Afghan talks but on commitments made by

the Taliban to combat terrorist groups and ensure Afghanistan is not used as a

staging ground for attacks on the U.S. and its allies.

Since signing the agreement, the Taliban have held

to a promise not to attack U.S. and NATO troops, but have carried out regular

attacks on Afghan security forces. The government wants an immediate

cease-fire, while the Taliban have said the terms should be agreed in the

negotiations.

Attacks, however, have continued unabated, with

civilians bearing the brunt of the violence.

On Friday, roadside bombs struck vehicles carrying

civilians in separate attacks in southern Afghanistan, killing 14 people,

including three children. No one has so far claimed responsibility for those

bombings.

Earlier last week, attacks — including a Taliban

truck bombing in northern Balkh province that targeted a commando base for

Afghan forces — left at least 17 people dead and scores more wounded.