Five years after Charlie Hebdo attack, Europe still faces threats

Fourteen alleged accomplices in the 2015 jihadist

attacks on the Charlie Hebdo satirical weekly and a Jewish supermarket go on

trial next week more than half-a-decade after days of bloodshed that still

shock France.

The attacks heralded a wave of Islamist violence

that has left 258 people dead. The violent wave, claimed by both Al-Qaeda and

the Islamic State terrorist groups, raised unsettling questions about modern

France’s ability to preserve security and harmony for a multicultural society.

People who escaped the massacres at Charlie Hebdo

and Hyper Cacher are set to give testimony next week and the process is set to

stir up memories of one of the darkest chapters in modern French history.

“This trial is an important moment for them,”

Marie-Laure Barre and Nathalie Senyk, lawyers for victims at Charlie Hebdo,

said in a statement to AFP.

“They are waiting for justice to be done to find out

who did what, knowing that those who pulled the trigger are no longer there,”

they added.

Among those who died at Charlie Hebdo were some of

France’s most celebrated cartoonists including its director Stephane

Charbonnier, known as “Charb”, 47, Jean Cabut, known as “Cabu”, 76, and Georges

Wolinski, 80

The Charlie Hebdo episode also raised questions

about the future of terrorism in Europe.

The terrorist threat against Europe has mutated in

the last few years as jihadist groups have seen their Middle East sanctuaries

eroded, but analysts say the West must remain braced for more attacks.

Both Al-Qaeda and ISIS — together responsible for

the highest-profile and most horrific terror attacks of the past two decades —

have lost potency as global organisations.

Dut despite splintering into branches and

franchises, their murderous ideology is still able to inspire individuals to

carry out random attacks in their name.

The murderous shooting spree, five years ago,

heralded an unprecedented wave of attacks in France.

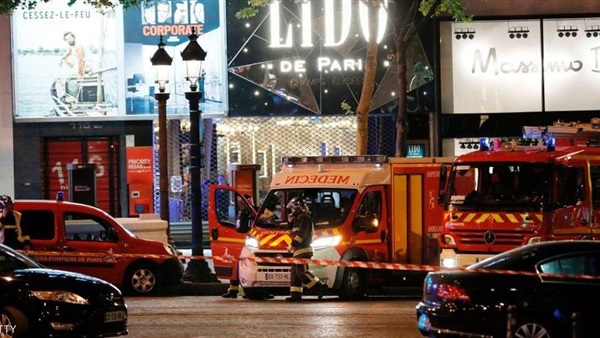

The deadliest were the coordinated attacks in Paris

on November 13 that year at the Bataclan music venue and other venues, when

gunmen killed 130 in a plan stemming from the ISIS group’s core leadership in

Syria.

Experts believe the same style of assault would be

unlikely to recur now, not least because ISIS has seen a dramatic loss of its

territory and membership in Iraq and Syria.

More typical this year were “isolated individuals

who were not spotted by the intelligence services… and their limited or even

non-existent contacts with identified jihadist networks,” a source in the

French anti-terror prosecutors’ office told AFP.

Since 2015, France has seen 17 crimes classified as

acts of terror.

Three took place in 2020, none of which were claimed

by the terror groups but were instead perpetrated by isolated individuals

suffering from psychological problems.

But anti-terror prosecutors still see signs of

operational coordination, including “networks of false documents and funding,”

the source said.

Seth Jones, director of the Transnational Threats

Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in

Washington, said that in recnt years, US and other military operations had “decimated”

the ISIS external operations network, killing or capturing many of its key

operational leaders.

Its military rout and the loss of territory ISIS had

declared as a caliphate in Iraq and Syria have also diminished its status, and

the motivation for individuals to carry out attacks in its name.

It remains possible that Al-Qaeda could carry out a

major attack in Europe, Jones said, either directly or through individuals

inspired by its ideology, though this was “not a high probability”.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have taken some focus off

terrorism for security forces worldwide.

But it has also complicated the task of the

jihadists, who have been active on a local level but very cautious about

ranging further afield.

“In general, the short-term terrorist threat has

risen in conflict zones and fallen in non-conflict zones,” a UN report said in

mid-July.

Plots continue to emerge, however.

German authorities said in April they had foiled a

plot to target American military installations, and arrested five Tajiks

suspected of acting in the name of ISIS.

Another source of risk comes from individuals

released from jail in Europe or freed or escaped from Kurdish-controlled

prisons in northern Syria where they have been held since ISIS was defeated.

Jean-Charles Brisard, head of the France-based

Center for the Analysis of Terrorism (CAT), does not rule out a new targeted

action by ISIS, pointing to recent attacks foiled in Europe.

“The next cycle will be that of those who are

leaving jail,” he said.

The CAT has established that 60 percent of prisoners

in France convicted over their actions in past conflicts in Bosnia, Iraq or

Afghanistan re-offended violently after their release.

A French security source, who asked not to be named,

said West Africa is a particular concern after France’s forces deployed in the

region in June killed the head of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM),

Abdelmalek Droukdel.

Eight people, including six young French aid

workers, were killed in a suspected jihadist raid on August 9 in Niger but no

group has claimed responsibility for the attack.

“I find it more likely that AQIM will conduct a

revenge attack against French forces or other French targets in Africa —

including North and West Africa — than in France itself,” said Jones. “It is

easier for the group to operate in Africa.”