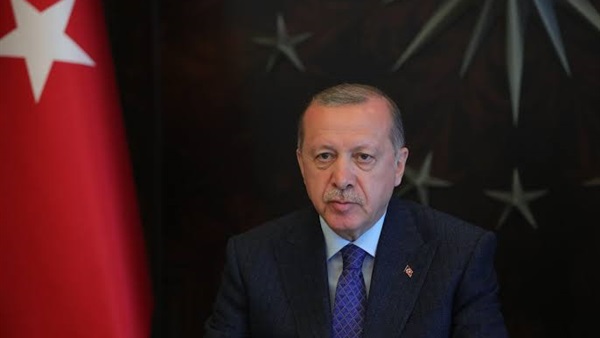

Erdoğan risking confrontation in eastern Mediterranean

Having

enjoyed some success in his efforts to spread Turkish influence in nearby areas

formerly part of the Ottoman Empire - Syria, Libya, Qatar - President Recep

Tayyip Erdoğan has set out to re-establish the Turkish dominance of the eastern

Mediterranean.

Unlike

efforts in Syria, which started with a focus on mediation that later turned to

confrontation, in the eastern Mediterranean Erdoğan appears set from the outset

on confrontational tactics in support of his strategic goal. That goal is

nothing less than Turkish dominance of the eastern half of the Mediterranean, a

necessary condition if he is to realize his overarching goal to establish

Turkey as the dominant power in the Greater Middle East.

As in other

measures, Erdoğan leaps backwards over Atatürk’s national security posture

focused on defending the homeland to the more wide-ranging posture of the

Ottomans that focused on expansion and domination of various non-Turkish

peoples, at least until Nationalism from within and rivals from without

dissolved their power.

Turkey under

President Erdoğan is using proxies to extend its power and influence, another

borrowing from Imperial tactics – the use of proxies, client states, and

subordinate allied forces was and is standard practice for imperial regimes. In

Libya, Turkey has sent Syrian national recruits alongside its own personnel; in

Syria, Turkey has recruited locals as well as accepted the service of foreign

fighters. How subordinate an ally Qatar proves to be by contributing personnel

to Turkish overseas operations remains to be seen.

The use of

proxies in the democratic age is even more beneficial than it was in the days

of monarchy – losing one’s own soldiers in foreign adventures can be costly at

the ballot box. And with modern air transport, proxies’ personnel can be easily

shifted to where the need is greatest, from the border region of Syria to

Libya, for example.

The use of

proxies to reduce the risk to one’s own personnel or to deny one’s direct

involvement in adventurism does not easily translate from the ground to the

high seas. Allied naval forces are not quite as compliant as land-based

militias recruited and maintained by one’s own supply chains. They have a

freedom of action, or decisive inaction, that land-based proxies find more

difficult to exercise. This explains, in part, why the Ottoman domination of

the eastern Mediterranean was always tenuous, dependent as it was on mariners

from subject nations such as Greece and Egypt.

Thus, if

Erdoğan tries to dominate the eastern Mediterranean through confrontation

tactics, continuing to resist mediation efforts undertaken by the EU and

others, he will be sending Turkey’s military assets and personnel into the

arena. Further, he will not be able to argue plausibly that any indiscretions

committed were done by forces not under Turkish command. Confrontational

tactics on the high seas carry a great deal of risk.

President

Erdoğan may very well risk it, for the only viable mediator between Erdoğan’s

Turkey and eastern Mediterranean nations is the U.S. That said, Erdoğan has not

shown interest in having the United States serve as an honest broker, only as a

supporter. Pompeo’s recent comments indicate a growing albeit subtle shift in

the U.S. views towards Turkey as a reliable and friendly collaborator. Turkey’s

continued refusal to pursue a positive relationship with Israel as its Arab

neighbors, and Muslim-majority Kosovo, are doing so has not gone unnoticed.

The EU cannot

be a mediator as both Cyprus and Greece are members of the EU, making it a

biased interlocutor that President Erdoğan would not accept to mediate

(negotiate with, perhaps, but not mediate).

Russia has

its own interests, and though Lavrov might offer to play the role of honest

broker, he is playing a hand in this high-stakes card game in the eastern

Mediterranean. For a time Turkey could rely on Russian support, but only until

Lavrov and Putin realize that Russian interests there do not align with

Turkey’s. Perhaps that would take some time, but it is hard to imagine that

Erdoğan would be so foolish to think that Russia could be a dispassionate

honest broker between Turkish and EU (Greece, Cyprus) interests given its own

interests in the region. The lesson of Syria is plain – Russia pursues its own

interests, always.

Perhaps

China, a major power distant from the region, could step in to mediate, but its

machinations in Hong Kong and regarding Covid-19 have revealed China’s lack of

ability at mediation and open negotiations.

It would have

to be a major power, for Erdoğan is unlikely to have much respect for minor

players in the geopolitical game, but the list is short and each seems to lack

the requisite unbiased attitude regarding the eastern Mediterranean disputes.

The U.N. could step up and fulfill its role to prevent conflict and resolve

disputes, but would President Erdoğan seek or accept their good offices?

It appears

that President Erdoğan will continue using risky confrontational tactics to

force the EU (Greece and Cyprus) to yield to his demands, if not in whole, at

least in part. This will lay the groundwork for later efforts to push the EU

and others aside little by little so he can realize over time his goal to

dominate the blue waters of the eastern Mediterranean.

It remains to be see whether in the midst of an election campaign, a looming fight for a Supreme Court nominee, and the ongoing response to the “Covid-19 pandemic, the U.S. White House will focus on the situation and muster the will to remind Erdoğan that Turkey is one subordinate ally in NATO and is expected to work with the other subordinate allies or to be prepared to face severe consequences from the Alliance’s only pre-eminent member.