Turkish foreign policy under Erdogan snared by short vision and militant tendency

The Turkish media was beating the drums of war in an

escalation of tensions with Greece over regional disputes and gas exploration

in the eastern Mediterranean on September 1. The pro-government media in

particular was rife with comments about how Turkey's military might outweighs

that of Greece and how Turkey would easily win in a potential war with its

neighbor. The same pro-government commentators and retired generals are now

praising the benefits of diplomacy and dialogue while accusing those who fail

to change the tone of encouraging tensions and war.

On this subject, the American Al-Monitor website published

an important report by Metin Gurcan, a writer and specialist on Turkish

affairs, in which he stated:

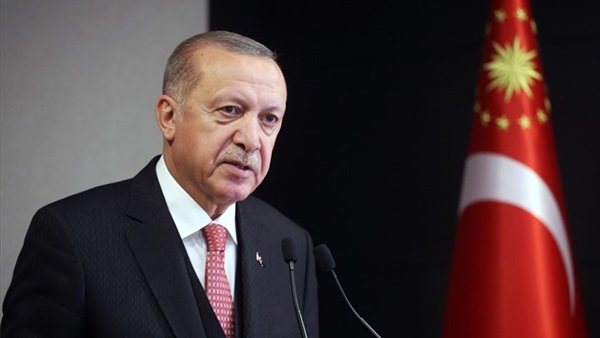

Such sudden turns on major issues of national interest have

become worryingly frequent in Turkey since President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

assumed great executive powers in 2018, indicating that Ankara's foreign policy

has fallen into a trap of short-term vision and is becoming increasingly

unpredictable.

Moreover, almost everyone in Ankara feels entitled to speak

on foreign policy matters. The president's spokesperson, the head of

communications, and the ministers of defense, economy, energy and interior have

all made comments. Shouting against Turkey's opponents is today a very common

thing in Ankara, and the clamor of politics seems to be that foreign affairs

has become an easy way for members of the ruling Justice and Development Party

(AKP) to project their images and promote their political life, usually without

risk but with high populist return.

Amid these frequent shifts and cacophony of messages,

foreign policy in Ankara today has become a world of contradiction and

confusion.

In the past two years, Erdogan has claimed credit for any

bold foreign policy move, including the Turkish military operation in

northeastern Syria in October 2019, Ankara’s maritime agreement with Libya the

following month, and efforts to assert its presence in Africa and the eastern

Mediterranean. But when it comes to ordering lesser-known events like

Washington's response to Ankara's purchase of Russian air defense systems,

President Donald Trump's loud message to Erdogan about Syria, the killing of 36

Turkish soldiers in a raid in Idlib, or Greece's militarization of the Aegean

islands near Turkey's shores, no one exists to be held accountable to the

public.

In short, foreign affairs has become a tool to boost

Erdogan's image, and the result is a very personal foreign policy.

On September 17, for example, Turkish presidential spokesman

Ibrahim Kalin formulated Ankara’s decision to withdraw an exploration ship from

the disputed waters in the Mediterranean as a personal gesture from Erdogan

toward Greece. “Our president has given an opportunity for diplomacy once

again, and we hope the Greek side will use this as an opportunity to push talks

ahead,” he said.

The dangerous repercussions of Erdogan's position in foreign

policy, which has come to reflect his short-tempered and polarized style in

domestic politics, are the erosion of institutional decision-making and

implementation in foreign policy matters. The institutional capacity of the

Foreign Ministry has been seriously damaged and overly politicized, including

through crony appointments and promotions.

Since 2018, the gap between Ankara's dreams or desires and

the reality on the ground or realpolitik has widened as well. Ankara has come

to pursue dreams of “games of spoiling” by others rather than a foreign policy

based on its economic and military capacity. The defensive inclination of the

status quo of Turkey's foreign policy in the past was not the best example, but

its current offensive and revisionist brand is devoid of grand strategy and

matching ambitions, making it extremely risky. Due to its failure to develop a

realistic, rational, and strategic framework, Turkey has become increasingly

isolated, trying to compensate for its perilous unity with revisionist military

activity.

Until 2010, Ankara had used only limited military force to

manage a complex and multi-threat environment. Its main priority was the

four-decade-old domestic conflict with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party

(PKK). Diplomacy and deterrence were also used to freeze rivalry in the eastern

Mediterranean and in the Cyprus conflict. This began to change in the summer of

2018 when Erdogan assumed sweeping powers under a new executive presidency

system.

Turkey's adoption of methods of might is rooted in profound

shifts in its foreign environment and domestic dynamics.

Abroad, Ankara's perceptions of the threat shifted east and

south due to increased security risks in the eastern Mediterranean, Iraq, North

Africa and Syria, in addition to strategic competition with Egypt, Russia,

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and other regional powers. Ankara was

particularly troubled by NATO's passivity on its southern side during the

Syrian crisis, which contributed to a security vacuum there. By relying on the

Syrian Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) to counter ISIS, Western powers

ignored or even dismissed Turkey's well-known concerns. Also, there is a pervasive

and enduring feeling among the Turkish ruling elite that the Western security

bloc failed to adequately support Ankara during and after the July 2016 coup

attempt in Turkey.

A number of domestic factors have also led to the

militarization of Turkish foreign policy. First, foreign policy became an

important item of Ankara's political agenda since the executive presidency

system came into effect. Military actions abroad enjoy strong popular support

and help maintain Erdogan's popularity. In particular, his embrace of a more

nationalist rhetoric at home helped cement his de facto alliance with the

extreme Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

Second, military deployments abroad are popular with the

armed forces themselves. It enhances morale and motivation through additional

pay and promotion opportunities, as well as provides valuable experience in

joint force operations.

The third domestic drive for Turkey's more militaristic

approach is its role in coordinating relations between the military and

civilian leadership, who both agree on the need to strengthen Turkey's military

capabilities and defense industry. The military is more interested in the

technical dimensions of this consensus as part of the transformation and

restructuring process called Vision 2033.

Meanwhile, politicians are keen to use this new capacity and

energy in domestic and foreign policy. They also hope that the continued

preoccupation of the military abroad will facilitate civilian control of the

army as the generals focus on foreign affairs rather than domestic affairs.

Finally, the boom in the Turkish defense industry allows Ankara to pursue a

more independent strategy and offer its defense systems for the purpose of

international marketing.

The basic problems of Turkish foreign policy today can be

summarized as follows: it lacks a grand strategy and succumbs to a short-lived

trap.

Turkey’s foreign policy has increasingly become a tool of

everyday politics at home, which has been shaped by a populist approach that

prioritizes domestic consumption and thus sticks foreign policy to the

government's domestic political agenda. It is also excessively echoing

Erdogan's polarizing and populist approach at home.

The field of foreign affairs has become entwined with

political career planning, as it is now easy to appoint AKP politicians as

ambassadors or other foreign positions.

In addition, the decision-making process often lacks

inclusive consultation and transparency, which leads to uncertainty,

arbitrariness, and unpredictability in foreign policy decisions.

All of Ankara's leading figures do not hesitate to get into

the realm of foreign policy, which often leads to messing up. For foreign

actors, especially those in the West, this could create confusion over who is

their interlocutor on the Turkish side and fuel a perception of a worsening

governance and management crisis in Ankara.

What will be the mood in Turkey next week on the ranks in

the Eastern Mediterranean? Does it remain in favor of dialogue or is it

reflected in provoking wars? These questions are becoming increasingly

difficult to answer, because seven days has now become a very long time in

Turkish foreign policy.