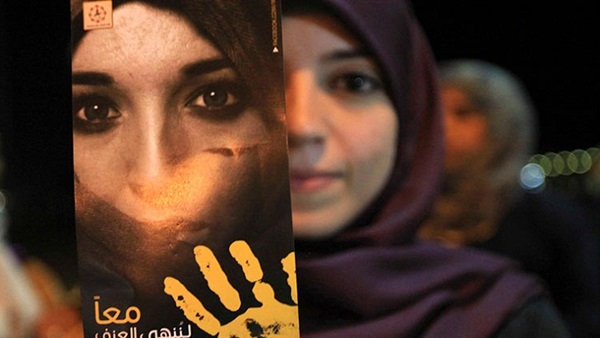

Libya’s women face many dangers for speaking out

In Libya,

for women’s rights defenders, even the dead are not permitted to rest.

The grave

of Hanan Al Barassi, a vocal critic of corruption and armed groups in the east

of the country, was desecrated just days after she was assassinated.

The

daughter of the prominent dissident lawyer posted pictures of the little shards

of shattered gravestone scattered on the ground.

Al Barassi

was gunned down in broad daylight in Benghazi’s busy city centre on Tuesday, a

day after she had posted on her Facebook page saying she was going to release a

video exposing the alleged corruption...

She was

startlingly open and brave in her criticism of the armed factions, which have

run rife across Libya in the war-wracked years since the 2011 demise of Muammar

Gaddafi.

And for

that she and her daughter had received numerous death threats, she was

eventually silenced, and her grave destroyed.

But Al

Barassi is not an exception. Her murder came just 16 months after the

disappearance of another prominent Benghazi woman, rights activist and

parliamentarian Siham Sergewa, who was kidnapped by armed men in the middle of

the night from her home, after openly criticising war on Tripoli. No one knows

what happened to Sergewa. Salwa Bugaighis, Fariha Barkawi and Salwa Yunis Al

Hinaid, all three of them prominent outspoken female rights defenders, were

murdered in 2014.

They are

part of a long procession of women in Libya, who are usually the most vocal

human rights defenders and for that have been threatened, assaulted, raped,

kidnapped, disappeared and murdered for speaking out.

Women who,

because they are women, are more vulnerable: they do not have powerful military

brigades and militias to protect them. Instead many of them are blamed for the

violence against them because they dared to step out of the “traditional”

gender roles and speak their mind. They are not even protected by the powerful

tribes they may hail from because few are willing to go out on a limb for a

noisy woman.

In the six

years that I have closely covered Libya, one of the most frustrating and

heartbreaking truths of the messy war-torn country is the absence of space

given to Libya’s highly educated and capable women and the dangers faced by

those who try to carve out an arena anyway.

Women, who have for years spearheaded Libya’s civil society movements,

are largely frozen out of the decision-making process at a potentially catastrophic

loss to the country. While there are female members of parliament and a

sprinkling of ministers, the internationally recognised presidential council

anchored in Tripoli is all male and headed up by Faiez Serraj.

Even in

the United Nations-brokered peace negotiations taking place right now, women

are woefully underrepresented: of the 75 Libyans participating in the latest

round of talks in Tunis, only a touch more than a dozen are women.

“Exclusion

of women has become the norm,” says Rida Al Tubuly, a pharmacology professor,

peacebuilder and founder of Together We Built It, which promotes inclusion of

women in the peace process.

She said

after addressing the UN security council last November about violence against

women and the need for freedom of expression, she was accused of being a spy

for foreign countries on social media groups and by a well-known Libyan TV

channel. She subsequently received death threats by people who said they knew

where she lived.

“We are

frustrated and disappointed with the international community facilitating the

process, that they are not gender mainstreaming what is coming,” she added.

She said

nothing underscored this issue more than the fact that Hanan Al Barassi was

murdered in the middle of the peace talks, and no one has been held to account.

“I am

calling on [the UN] to make sure this agreement incorporates significant

measures that protect women.”

Civil

society activist and lawyer, Hala Bugaighis, whose is the cousin of murdered

Salwa Bugaighis, said at the heart of the problem was the incorrect assumption

that women in Libya shouldn’t participate in the political area because it is

not their place and they are not qualified.

She

recently volunteered with the UN on a side-track to the ongoing negotiations

where women penned recommendations for the country. Around 120 women, many of

them lawyers and academics, laid out plans for transitional justice, saving the

economy and restructuring the military.

“We are

trying to push the UN to use these recommendations,” she added with frustration

in her voice.