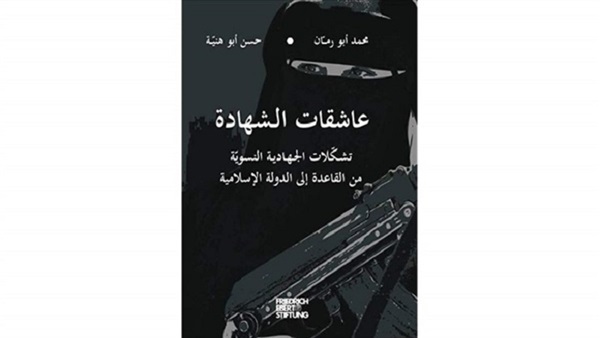

Infatuated with Martyrdom: Female Jihadism from Al Qaeda to Daesh

Saturday 13/October/2018 - 01:38 AM

Noura Bendari

The role of women jihadists has seen a radical shift with the emergence of Daesh and its declaration of a so-called “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria in 2014, according to a new book.

In their new book “Infatuated with Martyrdom: Female Jihadism from Al Qaeda to the ‘Islamic State’,” researchers Hassan Abu Hanieh and Mohammad Abu Rumman document the lives of a lot of women who joined Daesh, while exploring the stages and transformations of what has been termed “feminist jihadism”.

The book proceeds with a fundamental question that has confounded many: how can a bloody, patriarchical, or perhaps misogynist, organization attract hundreds of Arab and Western women?

Considering it a “quantum leap”, the authors answer such a query by digging deep into the phenomenon, monitoring the nature of women’s roles in Daesh and the religious discourse that tackle women’s participation in jihad, from Wahabism to Salafism.

“We maintained during our research that these women joined Daesh in a bid to regain a lost identity and contradict what they perceived as an enforced identity,” said Abu Hanieh during the launch of the book earlier this week.

He explained that European women who joined Daesh were more extreme than their Arab peers.

“It is ironic that women who received secular education their entire lives were the ones who are calling for the niqab, which covers the entire face, and not the hijab that only covers the face,” he said, noting that Arab women who joined the radical group did so in a quest to have more role within the “utopia” which Daesh has claims to have established.

In the book, the two authors draw significant conclusions, mainly that a major shift in the role of women in Daesh is being seen, with women moving from minor roles, like the “jihadis’ wives and entertainers”, to more leading roles.

“While attempting to study the surrounding environment of 47 women who left their homelands to become part of Daesh, many challenges have arisen, particularly the shortage of information and resources on the lives of these women,” said Abu Rumman, who noted that the “snow ball” methodology was used to track down the stories of each woman.

Al-Khansaa Brigade:

As IS began seizing control of large territories in Iraq and Syria, and with the declaration of the ‘Islamic State,’ it began to establish various institutions, commissions, and departments to manage the affairs of governance. Diwan al-Hisba is one of the most important departments tasked with ingraining IS ideology and way of life in society.

The women’s brigade also occasionally partakes in combat operations and plays a supporting role in the Army Department (Diwan al-Jund) and military aspects including providing medical services and preparing food for fighters.

The mission of al-Khansaa Brigade also includes security and intelligence work to detect and track down spies, both male and female. The Brigade’s membership includes women who migrated from Europe and Arab and Muslim countries, in addition to local Iraqi and Syrian women.

For Love of Martyrdom: Female Suicide Jihadism:

Suicide operations are a recent phenomenon introduced by secular and religious groups as a military stratagem of war and as a tactic to confront an adversary that has superior military weapons and capabilities with which it imposes control on land and people. Direct confrontation with such an adversary is impossible considering the imbalance of power, hence, resistance groups resort to suicide attacks. Global jihadist groups, from Al-Qaeda to IS, were late in adopting suicide attacks in their activities, hindered by the fierce debate among its ideologues and clerics regarding the religious permissibility of the tactic and its effectiveness. But when they did finally resort to it, global jihadist groups copied it from other secular, religious, and nationalist movements and ended up mastering it, relying on it increasingly until it became the prime military tactic in their combat strategy.

With the turn of the 21st century, global jihadist movement adopted suicide attacks as a primary war strategy, considering its effect in generating fear and terror, low cost of operation, and impact on enemies, according to jihadist discourse. Books, articles, and fatwas espousing its permissibility and preferability as a war tactic proliferated, to the point that almost all jihadist theorists and ideologues address the tactic within their writings on the rules of jihad. Hence, a vast volume of references has been made available to jihadist groups particularly addressing martyrdom operations and inghimasi acts (a term that has come to describe a fighter who launches a violent attack that ultimately ends up killing him or her, an act distinct from suicide missions).

Yet despite these numerous writings, it is rare to find in them discussion of women’s involvement in these operations, although the majority of this literature praises the perpetrators of these acts regardless of gender.

Despite the transformations witnessed in the role of women in jihadist circles, and the development of a female jihadist ideology that transcends the traditional domestic roles of jihadist women, nonetheless, the general nature of women’s roles in jihadist groups remains mostly confined to logistical support, as is the case with various countries that differ in the extent to which they allow their women in uniform to partake in combat.

The preferred nature of women’s jihad, according to jihadist ideology, remains that of the traditional domestic home caring woman who supports her family and husband and instills in her children the love of jihad and sacrifice, in addition to participating in building the jihadist society by actively engaging in media, education, health, moral policing, and logistical supportive roles.

Involving women in martyrdom operations, in most cases, emerges under pressure and appeals from the women themselves to carry out suicide missions motivated by the same motives that drive men toward such missions.

After prolonged debate, jihadist circles not only embraced the phenomenon, but exploited it as well, where the case of the ‘brave martyred woman’ became an effective form of propaganda and recruitment that shames ‘cowardly’ men into joining the ranks of male-dominated patriarchal jihadist groups operating within conservative and tribal societies.