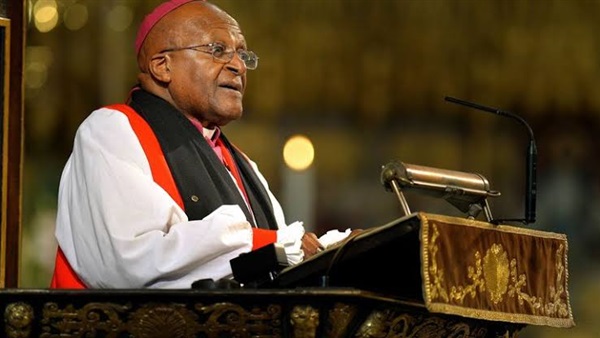

Desmond Tutu, Archbishop Who Helped End Apartheid, Dies

Desmond Tutu, an Anglican archbishop who led a global campaign to end South Africa’s racist policies and then helped in healing the nation’s wounds, has died. He was 90 years old.

Mr. Tutu’s death in Cape Town was confirmed in a statement from South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who didn’t say what the cause was. Mr. Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997 and had been hospitalized repeatedly in recent years.

“The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” Mr. Ramaphosa said. “He articulated the universal outrage at the ravages of apartheid and touchingly and profoundly demonstrated the depth of meaning of ubuntu, reconciliation and forgiveness.”

Known affectionately as “the Arch,” Mr. Tutu had mostly withdrawn from South Africa’s charged political scene, but used his rare public appearances—and his foundation—to hold his country’s new leaders to account. Announcing his retirement in 2010, Mr. Tutu had said he wanted to sip tea with his wife and spend more time with his grandchildren, and less in airports and hotels.

Short in stature, Mr. Tutu was a towering figure in South African politics.

With his friend and fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner, Nelson Mandela, he is credited with leading the charge against a white-minority government that was guided by a policy of racial segregation, known as apartheid. Still, after the African National Congress came to power in the 1994 democratic elections, he criticized the party for corruption and greed. As a result, Mr. Tutu became known as South Africa’s “moral conscience.”

As a bishop in the apartheid era, with police brutality roiling the country, he went from township funeral to township funeral preaching for peace. Mr. Tutu served as general secretary of the South African Council of Churches from 1978 to 1985, and his status in the religious community offered him protection from the apartheid government.

Sometimes Mr. Tutu’s sermons left people laughing; other times in silence. Once, he dove into a frenzied mob to save a suspected police informer from being burned to death. The crowd had thrown a gasoline-soaked tire around the man’s neck and was about to throw him into a burning car before Mr. Tutu pushed through to stop the killing.

His style was his own. Whether he was preaching for racial equality or for an end to the HIV epidemic, Mr. Tutu combined whispers with shrieks of delight.

“Wow, yippee!” he shouted after voting at age 62 in South Africa’s first democratic elections in April 1994, according to his memoir, “No Future Without Forgiveness.” A month later, he introduced Mr. Mandela as the country’s first Black president.

He later told reporters: “I said to God, ‘God, if I die now, I don’t really mind.’”

Born in South Africa’s North West province on Oct. 7, 1931, Mr. Tutu was brought up by his father, a teacher, and his mother, a domestic servant. When he was 12, his middle-class family moved to a small town called Ventersdorp, which later became the headquarters of the country’s most prominent white-supremacist group.

Mr. Tutu followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a teacher after graduating from the University of South Africa. A year later, he married a woman named Leah, a former student of his father’s.

Disillusioned with teaching in a South Africa’s inferior education system for Black students, Mr. Tutu accepted a scholarship to study theology at King’s College at the University of London. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees there. Living in England, away from apartheid, helped to rid him of the self-contempt that results from racism, he was quoted as saying in the 2006 biography “Rabble-Rouser for Peace.”

Mr. Tutu returned to South Africa in 1975, when many leaders in the fight against apartheid were living in exile. The resistance movement, still largely underground, faced new urgency. Mr. Tutu wrote to the South African prime minister in 1976: “The people can only take so much and no more.”

Two weeks later, protests by youths and schoolchildren in South Africa’s largest township erupted, and police responded with gunfire, killing hundreds.

In 1984, Mr. Tutu was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for spearheading the nonviolent movement against apartheid. But he saw himself first as a spiritual leader, and in 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from nearly three decades in prison, Mr. Tutu returned mostly to preaching.

There were notable diversions. After Mr. Mandela took office as president in 1994, Mr. Tutu headed South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a first-of-its-kind judicial committee that called on apartheid-era perpetrators to publicly apologize for their crimes to victims, who in turn shared their stories. Mr. Tutu’s embrace of both abusers and the abused helped bring together the newly democratic but fractured nation.

Mr. Tutu spoke on causes including gay rights, global warming and autocratic rulers. He called Zimbabwe’s longtime strongman Robert Mugabe a “cartoon figure of an archetypical African dictator” while other prominent African leaders shied away from taking a stance on Mr. Mugabe’s crackdown on the opposition.

“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor,” Mr. Tutu once said. “If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

This meant speaking out, even when it collided with institutions close to his heart.

In 2016, he supported his daughter Mpho’s marriage to a woman, despite the South African Anglican Church’s teachings that marriage was a union between a man and a woman. “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven,” he said.

Mr. Mandela once said that Mr. Tutu’s frankness, while not strategic at times, was vital to democracy. Mr. Tutu might have agreed. “Our world is a work in progress,” he told Oprah Winfrey in 2005. “It’s going to be OK.”

Mr. Tutu became more distant from South African’s postapartheid governing party, the ANC, whose officials he criticized for focusing on personal gain while much of the country still lived in poverty. In 2017, he and his wife, Leah Tutu, joined a nationwide demonstration calling for the resignation of the scandal-plagued president at the time, Jacob Zuma.

“Do you remember the price that was paid for our freedom?” he said at a 2009 memorial service for members of the ANC’s apartheid-era armed wing in Cape Town. “We had some fantastic young people. They paid a very heavy price. We all paid a very heavy price. And for what? So some of us can have three motor cars.”