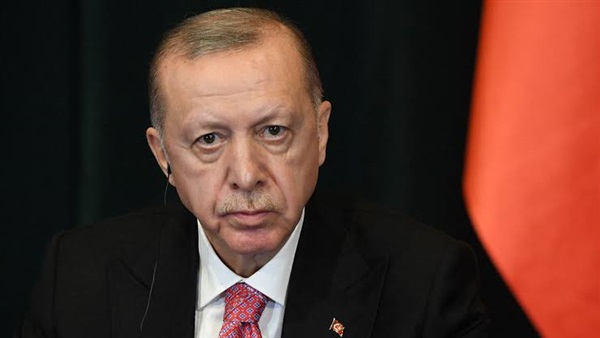

As Turkey’s economy struggles, Erdogan goes it alone

A parade of Central Bank governors have been fired, along with other bank policymakers who counseled fiscal prudence. Government ministers who once challenged dubious economic strategies are gone, replaced by others who seem to ask few questions and simply say yes.

As President Recep Tayyip Erdogan faces Turkey’s worst economic crisis in almost two decades, he has few independent-minded experts at his side — a consequence of his efforts to centralize power, which have sidelined or hollowed out financial institutions to which he once deferred, economists say.

The severity of the crisis came into sharp relief this month when the government announced that the annual inflation rate had reached 36.1 percent, the highest since 2002. That rise was driven by the rapid depreciation of the Turkish lira, which lost more than 40 percent of its value last year, and, more broadly, by Erdogan’s push to cut interest rates based on his unorthodox belief that this would lower consumer prices.

As financial hardship has spread across Turkey, the crisis has prompted fresh scrutiny of the president’s years-long accumulation of authority, from appointing university rectors to naming high court judges. But his vast powers are little help when it comes to the delicate task of managing Turkey’s economy, which in its current state requires a talent for reassuring global markets and investors — rather than the political skills and authoritarian inclinations that have long enabled Erdogan to outflank domestic opponents.

The president’s domination of economic policy may become a liability as he approaches elections next year. In a survey by the Turkish polling company Metropoll released in December, about 75 percent of respondents said their trust in the government’s economic policies had decreased over the past year.

For those who have watched Turkey’s development over years, including from inside the halls of power, the government’s current approach is a startling contrast to that of Erdogan’s early tenure, when he and members of his party largely deferred to technocrats carrying out reforms aimed at repairing an economy in ruin.

“The institutions are there to tell the truth to politicians,” said Hakan Kara, a former chief economist at Turkey’s Central Bank who left two years ago and now teaches at Ankara’s Bilkent University. Until recently, he said, there were “healthy checks and balances” that prevented the government from making crucial mistakes.

Now, “that kind of interaction is very weak,” he said. Seasoned economists said they were in the dark about whom the president asks for advice and where the economy is headed.

Three Central Bank governors were fired in a span of two years, along with other bank officials who were said to have opposed Erdogan’s interest-rate cuts. The dismissals were part of a pattern of political pressure on the Central Bank that has intensified over the past decade, marked by an increasing number of calls by Erdogan to cut interest rates, according to Selva Demiralp, a professor of economics at Istanbul’s Koc University and a former economist at the U.S. Federal Reserve Board.

“We have seen independence eroding,” she said. “And as political pressures go up, inflation deviates from targets.”

Turkey also has had four finance and treasury ministers since 2018, including Erdogan’s son-in-law. The latest, Nureddin Nebati, appointed in December, is considered a loyalist of the president and has become known for a string of eyebrow-raising statements, including a claim during a TV interview that the U.S. Federal Reserve is run by five families.

Erdogan has acknowledged the hardships caused by Turkey’s high inflation rate, calling it a “problem” while asserting that the country is better off than others around the world and insisting that its economic fundamentals are sound. Analysts say the economy has been buffeted by shocks both beyond its control and self-imposed, including the pandemic and a political dispute that led to a trade war with the United States.

“It is clear that there is a bulge in inflation, as in the exchange rate, that does not match the realities of our country and economy,” Erdogan told members of his ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, last week.

Emergency measures recently taken by the government have helped the lira recover some of its value against the dollar. And statements by Erdogan and the new finance minister over the past few days have suggested they intend to put off further aggressive cutting of interest rates. But it remains to be seen whether those measures will restore badly damaged confidence.

For some, the government’s recent signals only raise more questions about the president’s economic beliefs. “You have a theory that says you should cut interest rates to lower inflation rates. Then you say you are going to pause cutting interest rates when the inflation rate is 36 percent. Why would pausing establish trust?” Demiralp asked.

When Erdogan’s AKP assumed power in 2002 after a severe banking crisis, “they took over an economy that was basically bust,” said Cevdet Akcay, a former chief economist at Turkey’s Yapi Kredi bank. The new government — including Erdogan, who served as prime minister, and Ali Babacan, the economy minister — successfully implemented an International Monetary Fund assistance program that addressed structural problems in the economy, he said.

“The best ministers, the best Central Bank governor, by far the best secretary of the treasury that I have seen in my lifetime are during the AKP’s time,” Akcay said. “If they replaced their counterparts in the U.S., trust me, the performance in the U.S. would improve; they were that good. And Erdogan had no problem with any of this.”

Kara, who joined the Central Bank in 2002, said that under the IMF program, which was mostly prepared by Turkish technocrats, the banking system was rehabilitated, and foreign direct investment increased as trust in Turkey’s institutions started to improve.

“It was the best of all worlds,” he said, adding that Turkey’s economy was growing as inflation plummeted, from near 80 percent to 8 percent annually.

Others have said that Erdogan and his party — which clashed at times with the IMF over requirements of the program — had no choice but to implement it, given the state of the economy and the government’s strong desire at the time to join the European Union. And as the economy started to grow, benefiting the AKP’s vast patronage network, the government had no need to push back.

As late as 2010, Erdogan was heeding the counsel of advisers who cautioned that Turkey should seek to make growth more sustainable, because the economy was “borderline overheating,” rather than listening to ministers who wanted to maximize growth, Akcay said.

The situation started deteriorating gradually, economists said. Several key events occurred in 2013, notably the Gezi Park demonstrations — which began as a sit-in to protest the destruction of an Istanbul park and grew into nationwide protests against Erdogan’s government. The unrest jangled the nerves of foreign investors and fed Erdogan’s fears of plots targeting him.

The protests, just two weeks after Turkey had been elevated to an investment-grade rating by Moody’s Investors Service, “threw Erdogan off,” Akcay said. “Anybody around him who had close ties to the West became a semi-traitor or a traitor.”

But the “real breaking point” came after a coup attempt against Erdogan’s government in the summer of 2016, Kara said — an event that was followed by a massive campaign of arrests and a purge of state institutions.

“Power become more and more centralized. The people appointed to top positions were selected from a very small pool,” Kara said. At the Central Bank, concerns about political pressure became more acute, and the bank, like other institutions, was expected to “follow instructions from the government very closely.”

Amid the latest economic crisis, Erdogan has framed developments, including the plunging value of the lira, as calculated steps designed to foster export-led growth, increase access to credit and reduce the country’s trade deficit. This explanation is part of a populist pitch ahead of the 2023 elections.

“No one would object to the idea that the Turkish economy should be more self-sufficient,” said Demiralp, adding that the net value Turkish exports add to the economy is “very low” because of the high cost of intermediate goods. But to improve the trade deficit, “you need … innovation,” she said. “Doing it through monetary policy is not the way to go.”