Australia to launch rescue mission for women and children trapped in Syrian detention camps

The Australian government is preparing to launch a mission to rescue dozens of Australian women and children trapped in Syrian detention camps.

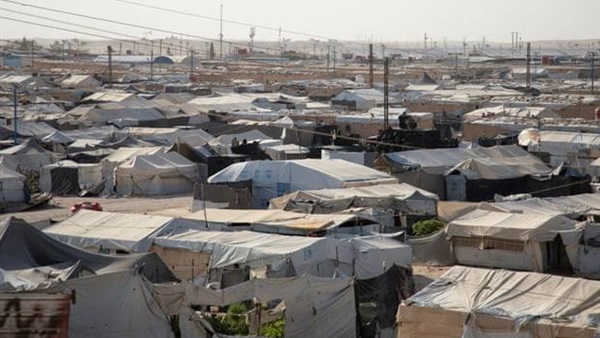

More than 20 Australian women and more than 40 children – the widows, sons and daughters of slain or jailed Islamic State combatants – remain within the al-Hol and Roj detention camps in north-east Syria.

Australia will repatriate more than 20 of its citizens, most of them children, but will not be able to bring all Australians out of the camps at once. Subsequent operations are expected in coming months.

Many of the women held in the camps say they were coerced or tricked into travelling to Syria by husbands who have since died. Most of the Australian children are under six; several were born in the camps.

In 2019, Australia launched a secret rescue mission to repatriate eight Australian orphans, including a pregnant teenager, from the camps. But since then the government has refused to bring any more home, citing security concerns.

The Guardian has confirmed with multiple sources that a rescue mission is impending.

A spokesperson for the home affairs minister, Clare O’Neil, told Guardian Australia on Sunday: “The Australian government’s overriding priority is the protection of Australians and Australia’s national interest, informed by national security advice. Given the sensitive nature of the matters involved, it would not be appropriate to comment further.”

Most of the Australians – including 44 children – are held in the Roj camp, closer to the Iraqi border. It is considered safer than al-Hawl, but malnutrition, illness and violence are common.

Al-Hawl, where one Australian family group and several children with a right to Australian citizenship are held, is considered exceedingly dangerous, with IS still active. More than 100 murders were reported in the 18 months to June this year.

The largely Kurdish, US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces last month arrested more than 300 IS operatives inside al-Hawl, seized weapons and liberated at least six women found hidden and chained inside the camp, who had been tortured by IS over years. One of the women had been captured in 2014, aged nine.

“IS has depended mainly on women and children … to maintain the Isis extremist ideology and spread it in the camp,” troops who led the raid on al-Hawl said.

Other countries with nationals inside the Syrian camps have been steadily repatriating them.

Germany has repatriated 91 of its citizens, France 86 and the US 26. Kazakhstan has returned more than 700 of its nationals, Russia and Kosovo more than 200 each. France is running an operation repatriating its citizens, including orphans.

The removal of foreign nationals has the support of the Kurdish-led forces which, for now, have control of the camps. The US, which has a significant military presence in north-east Syria, has repeatedly pushed Australia to repatriate its citizens.

Australian children have suffered acutely in detention in Syria.

The family of Sydney-born teenager Yusuf Zahab was told in July that he had died of uncertain causes. He had previously contracted tuberculosis and had sent desperate pleas for help during an IS siege of al-Sina’a prison, in al-Hasakah, in January 2022. He was 11 when he was taken to Syria.

In 2021, an 11-year-old Australian girl collapsed due to malnutrition in al-Roj camp. And in 2020, a three-year-old Australian girl suffered severe frostbite to her fingers during a bitterly cold winter.

One Australian held in Roj camp was 14 when she was trafficked into Syria and forcibly married to an IS fighter. She has since given birth to four children.

The women in Roj camp have volunteered to be subject to government control orders if they are returned.

UN experts, led by Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism, have told Australia the repatriation of women and children is “entirely feasible”.

“The government of Australia has the capacity to do so,” they said. “Many other governments are currently doing it. Australia has an advanced child welfare, education, criminal justice and health system which is eminently capable of addressing the needs of these children and their mothers.

“Failure to repatriate is an abdication of Australia’s treaty obligations and their deeper moral obligations to protect Australia’s most vulnerable children.”

The president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Peter Maurer, said already “appallingly harsh conditions” in al-Hawl were growing worse.

“The children here have less food, clean water, health care and education than international standards call for. They are endlessly exposed to dangers, and their rights are ignored. A lack of attention is not an excuse to forget the women and children here.

“We welcome the efforts that have been made to repatriate women and children back to their home countries. But this camp remains the shame of the international community.”