Tutankhamun: how the boy king became Egypt’s most famous pharaoh

Ancient Egyptians did cancel culture in a very big way. When the pharaoh Horemheb came to power around 1319BC, he immediately set about eradicating the names of his predecessors, destroying temples, usurping monuments and desecrating tombs.

For some reason or other, however, he spared the resting place of one former pharaoh and left it to the sands. More than 3,000 years later, the inhabitant of that tomb became the most famous pharaoh of them all.

Tutankhamun would have been an unlikely contender for this title. A child king, small, frail and curtailed by an untimely death, other pharaohs were more powerful and more consequential. How did this ephemeral and erased boy come to enrapture the world?

For starters, Tutankhamun’s family history was seemingly pretty colourful, though evidence is rather limited.

“Firm facts about these ancient individuals are as dry as an abandoned canal compared to the soap opera psychodrama that has been woven around them,” writes Professor Christina Riggs of Durham University in her book Treasured.

The family tree we can piece together is pure Game of Thrones. Tutankhamun is thought to be the son of the pharaoh Akhenaten, whose wife Nefertiti might have been his own first cousin on both sides.

Tutankhamun’s mother was not Nefertiti but another woman who might have also been his aunt. When he took the throne, he himself married the 13 year-old Ankhesenamun, who was probably his half-sister.

With this level of inbreeding, Tutankhamun was unsurprisingly unhealthy. Of slight build and 5ft 6in in height, he had a cleft palate, scoliosis and possibly a clubbed foot. Several walking canes were found in his tomb. His mummy, meanwhile, is riddled with the DNA of malaria, suggesting repeated reinfection. Some think he also had sickle cell anaemia.

It was never going to be a long reign but, to understand it, one must first consider that of his father.

Akhenaten had been revolutionary in launching something known as the Amarna period. In this, he abolished Egypt’s polytheism and established a new cult of Aten, a sun god.

It’s not clear why Akhenaten did this. It could have been philosophical, he could have been consolidating power or both. He certainly pursued the latter, building the new capital of Akhetaten while closing temples elsewhere and disrupting the economy around them.

In honour of this new god, a new prince was called Tutankhaten.

When this nine-year-old boy ultimately came to the throne around 1332BC, he was similar to our own Edward VI, successor to Henry VIII: a boy king of questionable health whose country had been turned upside down by his father.

Whereas Edward and his advisers pushed religious reforms further, King Tut and his counsellors set about putting his father’s whole project in reverse.

This began almost as soon as Akhenaten died, though it was perhaps a few years before the prince succeeded.

The old gods were restored. In honour of Amun, sometime king of the gods, the new pharaoh renamed himself Tutankhamun. Great building projects were mounted for the renewed religion. The monarchy had also returned to the traditional capital of Thebes.

We don’t know how much influence Tutankhamun’s advisers had or if he was interested in governing, but it was an active reign across the whole empire. Expeditions were mounted in the east and campaigns were fought in the northeast and in Nubia to the south.

It was a reign of some consequence, but brief. It is unclear how he died but he is thought to have been 18 or 19 and had been in power for about nine years.

His association with the Amarna period was enough to bring about his suppression by Horemheb. He was forgotten until fresh discoveries in the late 19th century.

However, it was the irony of ironies. The erasure of Tutankhamun had been so successful that grave robbers were unaware of his existence and therefore did not seek his tomb. His removal from history guaranteed his place in it.

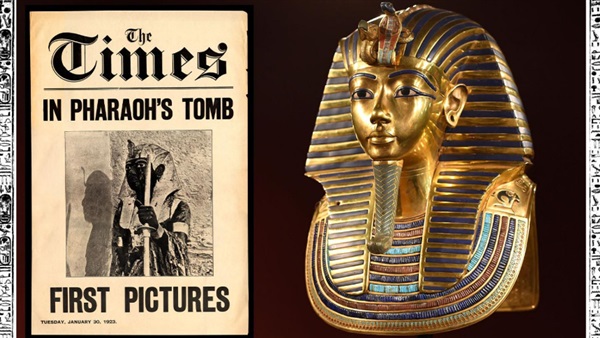

Through the discovery of his tomb a century ago, Tutankhamun is one pharaoh who has had an afterlife, both a sublime and ridiculous one.

First came Tutmania, where he drove the sale of Tut-tat worldwide. Cigarette boxes, soap brands, Hollywood movies and cars all took on an Egyptian flavour. However, Tutankhamun has done more in the last century than flog stuff.

Riggs has described Tutankhamun’s “second career as a cultural ambassador”. The young pharaoh was a ready made symbol for the new, independent Egypt of 1922, but became almost like a diplomat after 1961 when his artefacts went on five separate global tours, seen by tens of millions, including at the British Museum in London in 1972.

“The objects are treated as if he is a person,” Riggs said. “It’s like a visiting dignitary. They travel on military planes and ships and are greeted in the highest security and military parades.”

These shows helped Egypt cement relations with other countries and to display itself on the world stage. All the while, the boy pharaoh was once again being treated like royalty.