Afghan fields come back to life as charity channels water for crops

Marjana remembers the last time “the hunger” came to her village in Ghor province, more than 50 years ago, before even the Soviet invasion. “I was seven years old and my father sold me for marriage,” she said. “He was 50 years old. I was the second wife. At first, I was more like a labourer. I was a child and did not know what to expect.”

Much has improved in her village since she was a young girl. Parents no longer sell off their daughters or give them in marriage before they are 18 years old. Many of them have gone to school.

And in the half century since the epic famine that saw her sold off as a child, such conditions have not returned to their corner of Afghanistan — until now.

For the past two years, the crops they have planted in the fields fed by irrigation channels have failed because of successive droughts once only seen in a generation, like that of Marjana’s youth.

It was Marjana’s parents who brought their people here from their ancestral village in Wardak province, where they were too poor to afford land.

In Ghor, they found land just outside the provincial capital that was going cheap, but needed irrigation channels dug to make it viable. The water ran down to the channels from the hillside above the village, as the deep snows of winter slowly melted in the spring.

Over the years, however, the villagers noticed that the winters were warming and the snows were not lying so deep. “There used to be a metre of snow here in winter,” Akbar Khan, 65, says, gesturing to the pasture. “It would melt slowly as the spring came and seep into the ground, making it perfect for growing.”

As the winters warmed, however, less snow fell and it melted away more quickly. After the drought came, the spring rains fell in a torrent on the parched land, which could not absorb it, leading to flooding. “It was flood or famine,” Khan said.

The villagers had heard little of the science of climate change but they were feeling its dramatic effects, having noticed the changes taking place over decades.

Despite being one of the lowest emitters of greenhouse gases in the world, Afghanistan is in the top ten countries most vulnerable to climate change. Winter snow is crucial for agriculture: in the highlands like Ghor, the snow acts as a reservoir, melting in the summer season and providing water for irrigation. If the summer or spring is too hot, fast melting can cause disaster downstream, a lack of irrigation water in the summer and flooding.

This was the situation in which Afghanaid found Pozalig when they arrived last winter to examine what had tipped the village into a state of crisis.

At that point, having lost two years of crops, most villagers were subsisting on emergency food. Some families had sent men to Iran to seek employment, a traditional coping mechanism in this part of the country. But the economic crisis there, together with growing hostility towards Afghan refugees, had shrunk opportunities.

Emergency food supplies were needed to get people through the immediate crisis, but Afghanaid recognised that future planning needed to be done to tackle the climate-change issues.

“We can’t just keep going on year after year distributing these huge amounts of food to people,” Charles Davy, the managing director of Afghanaid, said. “Yes, we’ve got to meet the emergency needs as they are, but the only way out of this crisis is that people can grow their own food again.”

In Pozalig, Afghanaid engineers began looking at what could be done to manage the watershed and irrigation from the snowfall on the mountain, slowing it down to prevent flooding and channelling the water through agricultural land.

Farmers who had lost their crops were set to work under their direction to rehabilitate old irrigation canals and construct new ones to manage the snow melt coming down the mountain. In fields previously only good for grazing, they planted fruit orchards, high-yield crops that could both feed the village and provide a cash crop to sell.

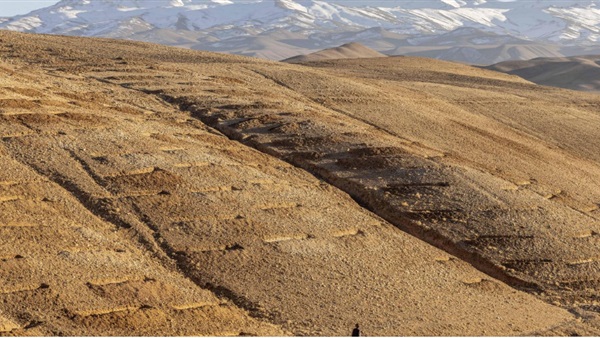

On the hillside round the village the men dug a series of contour trenches to slow the water runoff in the spring and keep their field irrigated. As the first snows fell on the hills late last month, villagers proudly showed off their new irrigation systems and the saplings planted in the fields. By the village, ducks dabbled in the stream re-fed by the water management system.

Marjana says she has heard stories from other villages of girls being sold off by families who can no longer feed them, just as she was 50 years ago. “I will never let that happen here because it happened to me,” she said.

“But now I see that our fields are coming back to life, I pray no one will ever have to think of it again. We know we cannot change the climate, we cannot change the snow. But we must adapt and make it work, for our children’s sake. That is why our parents brought us here.”