Why Putin’s raw recruits are no match for Ukraine’s western tech

At about midnight on New Year’s Eve a barrage of

American-built Himars missiles smashed into a building packed with Russian

conscripts in Makiivka, just outside Donetsk in occupied east Ukraine.

The Professional Technical School was not a well-chosen

sanctuary: it stood out even on commercial satellite imagery as the most

prominent building for miles around. Despite that, Russian commanders had

filled it with recruits and apparently stored ammunition in the basement. They

never stood a chance.

The Kremlin has acknowledged that 89 servicemen were killed

and blamed its own soldiers’ use of mobile phones for giving their location

away. Other estimates, from the Ukrainian armed forces and on Russian military

social media, have put the death toll in the hundreds.

To many ordinary Russians, the incident is simply

unforgivable. To President Putin it is the latest evidence that his invading

army is structurally inept and organisationally weak. It also points to the

most critical issue for the coming year. Wars measured in years become contests

in organisational learning and adaptation; eventually it’s the difference

between victory and defeat.

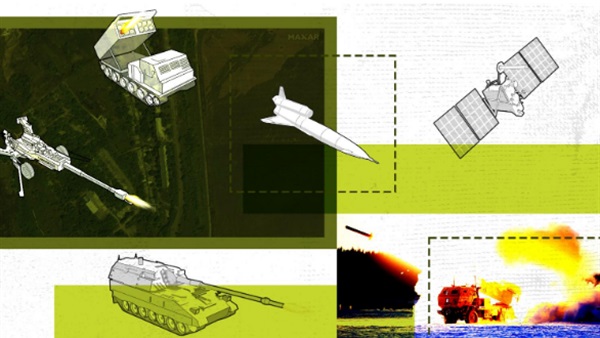

West’s weapons tilt the balance

The Ukrainian armed forces have been learning the western —

that is, the Nato — style of warfare since their capitulation to Russia’s first

land grab in 2014. Since last February they have been learning and adapting

very fast. They had already created a “combined arms” approach to operations —

integrating intelligence with air power, missiles and ground forces operating

flexibly in relatively small units. Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite system was

made available to them and has given Kyiv’s generals the philosopher’s stone of

command and control – a system that offers so many cheap satellites over a

small area, the enemy can’t stymie it or take it down. It provides instant

connectivity for everyone from the central headquarters to the muddiest

trenches. All armies strive for this, but until now no one has had it for real.

Starlink has got western defence chiefs looking hard at their own existing

plans.

Ukraine was able to hold off the early Russian attack and

buy time to reorientate its forces. Over the summer they absorbed more western

weapons systems that allowed them to put pressure on Russia’s biggest weak

spot: its creaking logistics chain. Few weapons on a battlefront are real

game-changers, but the long-range Himars system comes close for its ability to

hurt Russian forces far behind the fighting. So too does Nato’s flighted

Excalibur artillery shell, which turns a standard howitzer into a precision

weapon.

Kyiv still has some way to go before it has enough equipment

and troops to conduct the sort of offensive that will throw Russian forces out

of most, or all, of its territory. It needs a lot more of what it already has —

and then more overtly offensive weapon systems, including heavier armoured

forces, more attack aircraft and more drones and missiles.

The 50 Bradley Fighting Vehicles the US is sending to

Ukraine — the best in the business for supporting tanks in an offensive — plus

the recently promised German Marder and French AMX-10 armoured vehicles will

help, but are not enough.

A new, new model army

Having failed to win the war quickly with its creaking

standing army, Russia is trying to build a new force, probably on the basis of

near-continuous mobilisation, which must be trained and equipped by the spring

in time for a big offensive envisaged by its overall commander in Ukraine,

General Sergey Surovikin.

Can it be done? It’s been done before.

In 1645, facing repeated incompetence, Thomas Fairfax and

Oliver Cromwell built parliament’s New Model Army in months. There were no

great technical or tactical revolutions, just the creation of a professional,

regularly paid, well-equipped force. It embodied Cromwell’s maxim: “A man must

know what he fights for, and love what he knows.” It numbered at its peak no

more than 30,000 infantry, cavalry and dragoons. But after an initial setback

in the West Country, the New Model Army was never defeated.

In 1914, Britain’s “old contemptibles” in the British

Expeditionary Force were struggling to hold the line in Belgium. Lord Kitchener

began recruiting a citizen army for a war that he, at least, realised would not

be over by Christmas.

Kitchener didn’t believe a conscript army would be

effective. He was building a citizen force of free and patriotic volunteers. He

directed the generals to operate conservatively until his citizen army was

ready for a war-changing push. The recruitment target of 500,000 had grown to a

force of two million by mid-1916.

On July 1, 26 days after his death, Kitchener’s Army went

into action on the Somme. That first day was famously a disaster, but his

citizen army learned and adapted, and eventually it prevailed, equal partner to

the French army.

More than Kitchener’s Army, Stalin’s Red Army had to remake

itself even as it was fighting. His pre-war army was destroyed when the Germans

attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. German planners had assumed that the

Soviet Union might be able to put 300 new divisions into the field. In fact, by

December 1941 the Soviets had created the equivalent of more than 600

divisions. Inevitably they lacked almost everything, but 1942 was a year of desperate

adaptation. In two months, 25 new tank corps were formed. Almost a million were

recruited straight from the gulags. They frequently attacked without rifles —

soldiers were told to take one from whoever was dead. Through the sheer

brutality of the process, the Red Army developed its own version of the German

blitzkrieg: successive hammer blows of one unit after another.

Raw recruits in line of fire

Ultimately armies are a reflection of their societies. As

Putin’s Russia tries to recreate an army that can fight Ukraine — where

everyone certainly knows what they fight for, and obviously loves what they

know — it will have to overcome some of the deepest societal roots of its

present ineptitude.

To be more effective for Surovikin’s spring offensive, the

re-mobilised Russian army will have to be less corrupt, a characteristic that

bedevils the quality and supply of military equipment. It should have a much

stronger cadre of non-commissioned officers — the practical backbone of any

army. Its logistics need to be modernised quickly. Food and ammunition supply

is particularly acute.

More fundamentally, a new Russian army needs to be able to

operate in a less centralised way. Big units of anything, sitting in one place

for any length of time, are asking to be targeted, as in Makiivka. A modern

army has got to be able to take care of itself in small units but stay closely

connected to its central command. Not least, it isn’t clear that the limited

Russian training establishment can deal with a throughput of recruits that has

doubled since last summer.

These structural issues are impossible to resolve fully in

so short a time. When Surovikin’s new forces reach the battlefront, however,

some improvement in Russian organisation and fighting power seems plausible. He

may assume they will adapt quickly in combat. But on the ground, at least , Surovikin

will still be commanding a largely 20th-century Soviet-style army up against an

increasingly 21st-century Ukrainian combined force.

Perhaps he will have no option but to keep throwing his

troops into the line of fire like the Red Army once did, testing the longevity

of the grim dictum ascribed to Stalin: “In warfare, quantity has a quality all

its own”.