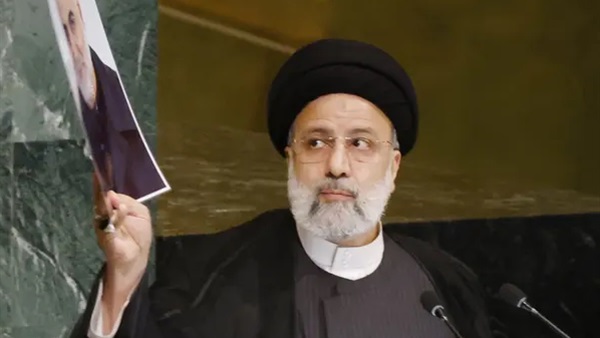

The Observer view on averting the west’s collision course with Iran

A ceremony in Tehran last week marking the third anniversary

of the assassination in Iraq by a US drone of Qassem Suleimani, a senior

commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), conveyed a defiant

message to the west. “We have not and will not forget the blood of martyr

Suleimani. The Americans must know that revenge is certain and the murderers

will have no easy sleep,” Iran’s hardline president, Ebrahim Raisi, vowed.

Iran has already attempted to avenge Suleimani’s death

through what US officials say was an IRGC plot to kill John Bolton, Donald

Trump’s former national security adviser. It is demanding the arrest of more

than 150 American and British “suspects”, including Trump, who ordered the

drone strike. Tehran has also imposed sanctions on western officials and,

bizarrely, the RAF base at Menwith Hill, North Yorkshire, which it claims

assisted the strike. The UK is expected to follow the US in designating the

IRGC a terrorist group.

The evident depth of anger and enmity felt within Iran’s

regime over Suleimani’s killing and many other long-festering grievances is not

wholly surprising, yet it should give western governments pause. It fuels an

evolving, many-fronted threat to western security interests. It also reflects a

huge strategic defeat: the failure of a decades-long US and Europe-led policy

of engagement and the consequent emergence of the Islamic Republic as an

implacable foe.

Bad blood may be traced back to the 1979 toppling of the

Shah, a key US ally. Israel views Iran as an existential threat. Its backing

for Syria’s dictator and anti-western Shia militias in Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq

is seen as all of a piece.

The risk of open confrontation with the west is further

aggravated by three explosive issues. One is the anticipated collapse of

long-running talks to deny Iran nuclear weapons-making capabilities. If diplomacy

fails, the prospect of military action by Israel is real. A second source of

added tension is Iran’s supply of “kamikaze drones” to Russia for its war in

Ukraine. On Friday, the US slapped yet more sanctions on Iran in bid to curb

this dangerous escalation.

Most threatening of all perhaps, at least from the mullahs’

perspective, is culturally and ideologically destabilising support across the

western world for the ongoing struggle for women’s rights inside Iran – and for

an end to executions, torture, censorship and clerical repression. Like their

peers inside the country, thousands of demonstrators gathered in London this

weekend to demand a new, free Iran. The old order trembles.

Was Iran’s descent into domestic tyranny and international

pariah status inevitable? Moderate presidents Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and

Hassan Rouhani (2013-21) encouraged hopes of rapprochement with the west and

more progressive policies at home. That they ultimately failed was in part

attributable to the hostility of hardliners and conservative control of the

Majlis (parliament).

Would-be reformers also struggled with a powerful, corrupt

IRGC and the baleful influence of its chief, the fiercely anti-American supreme

leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. It is at him, principally, that the wrath of

those protesting against the death of Mahsa Amini is aimed. If Iran is to

change, they rightly insist, Khamenei must go.

The regime’s slide into lawless illegitimacy is Khamenei’s

dire legacy. So, too, is a succession of bad foreign policy choices, typified

by his “look east” strategy favouring ties with Russia and China over the west.

Yet policy mistakes and complacency by politicians in the west have also

contributed to the crisis.

Barack Obama tried hard to make engagement work. The result

was the 2015 nuclear deal. But Republicans in Congress blocked the

across-the-board easing of sanctions that Tehran expected. That failure to

deliver undercut Rouhani and the reformers politically as Iranians’ economic

plight inexorably worsened.

Western policy further shredded with the advent of Trump.

Egged on by Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s hard-right prime minister, he reneged

on the nuclear deal in 2018. Iran has since greatly increased its

weapons-related capabilities. What Trump and Netanyahu said they most feared –

a nuclear-armed Iran – has been brought closer by their political machinations.

Obama’s decision not to intervene directly in Syria’s civil

war left the door open to the IRGC and its ally, Russia. Likewise, the west’s

failure to seriously address the Israel-Palestine conflict allowed Iran’s

hardliners to grow their influence with Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza.

Meanwhile, Israel’s escalating “shadow war” brought a series of provocative

assassinations of Iranian officials and scientists.

With Iran now positioned as Russia’s major wartime ally, the

potential for these various strands of conflict to merge into a large

confrontation is obvious. Yet, surprisingly, there is little discussion in

western countries about what to do. Do the US and its allies seek regime change

in Iran? If so, do they plan to actively assist the protesters?

If not, then a rethink is urgently required about how best

to rebuild a constructive dialogue with the majority of Iranians who reject

their country’s increasingly desperate, illegitimate leadership – and dream of

a prosperous, democratic future. What, exactly, is the west’s policy towards

Iran? A fresh start is needed, before it’s too late.