Ennahda Movement and the end of the era of Islamist groups

The intellectual and doctrinal transformations that have

afflicted Islamists in general following the Arab Spring are very numerous, but

the Muslim Brotherhood, as the largest of these groups, has suffered the most

in this regard.

The sectarian religious character of the Muslim Brotherhood

makes it consider itself as the only group of true Muslims, that it alone possesses

the truth, and that it is what was intended by the Prophet Muhammad (peace be

upon him) in the hadith: “whoever parts from the Jama'ah (group) the measure of

a hand-span, then he has cast off the yoke of Islam from his neck,” thus

necessitating allegiance to it. Prominent Syrian Brotherhood member Sa’id Hawwa

wrote in his books that the Muslim Brotherhood most closely embodies the

characteristics of the Muslim community and that Muslims should follow the

thought of Hassan al-Banna.

Ennahda Movement and the Brotherhood of Tunisia

It is a different matter for the Ennahda Movement, the

political arm of the Brotherhood in Tunisia, as Rached Ghannouchi expressed in his

book that the movement was the fruit of the interaction of three elements in

various degrees.

The first element referred to traditional Tunisian

religiosity, including the Maliki school of jurisprudential thought, the Ash’ari

creedal beliefs and Sufi discipline. The second element was the Salafi-Brotherhood

religiosity from the East and the rational religiosity that was swept up by the

wave of Salafi-Brotherhood religiosity. He followed that way for a while but

then stopped, searching, and he discovered in stages that the Brotherhood was

the biggest obstacle to the advancement of Islam. Then he adopted the principle-based

understanding of Islam and rehabilitation with the West and the leftist

ideology, and he did not adopt the Brotherhood standards of dividing the people

into believers and disbelievers but instead on the basis of political and

social criteria: patriot, traitor, revolutionary, reactionary, peasant, feudal.

He rehabilitated the reformist school in Tunisia and finally defended the

isolationist method in dealing with Islam and the opposition currents.

Ennahda is similar to the Brotherhood of Egypt regarding

publicity and secrecy in action. The Brotherhood's burden was not only

represented in the founding texts, but also in the historical load that the

group has carried out since Banna founded the paramilitary “Special Apparatus”

in 1940 and established a special understanding of allegiance. The group had both

a public and secret composition, and this duplicity of resolve between what is

secret and what is public is manifested in Ennahda as well, which prompted some

of its senior founders to suspend their membership, as is the case with

Abdelfattah Mourou, the co-founder and vice president of the movement.

The most important difference is that Ennahda did not

include Islamic Sharia law in its electoral program. It also accepted the first

chapter of the Tunisian constitution of 1959, which states that Tunisia is a

free and independent state, its language is Arabic and its religion is Islam.

Ghannouchi sees that the Tunisian society agrees with this

in accordance with the constitution, while raising the issue of the Sharia would

divide it into two camps: one for the Sharia and another against it, and he is

for putting unity over division. Just as the Sharia and its application in some

Arab countries have made it an object of confusion, as it is often utilized

against rights and freedoms, against women, against the arts and against

non-Muslims, a part of Tunisian society may be apprehensive of Sharia, which

makes Tunisians unwilling to put a part of society outside the Sharia or in

opposition to it just because they have questions about it.

Ghannouchi views the purposes of the Sharia, which are aimed

at the freedom of people, are what his party calls for, and he does not see Sharia

as a punishment.

The state and the problematic application of Sharia

Mourou went on to say that the building of the state is

based on the application of Sharia, which no one advocating it has a clear

vision of how to apply it. He criticized Islamist currents’ use of the slogan “Islam

is the solution” without presenting programs that translate this slogan into

reality.

Ghannouchi and Mourou do not speak of an Islamic state. Instead

they are speaking of a democratic state and the authority of the people, who

choose their representatives, with nothing being imposed on them they do not

want. Ghannouchi offers a vision of partial secularism that makes the state a

neutral body for all its citizens. He wants to liberate religion from the

state, so that the state does not speak in the name of religion, and he also sees

the distinction between what is religious and what is political.

Conclusion

The two movements did not play active roles in the Tunisian

or Egyptian revolutions exploding, but rather only participated after the youth

spontaneously onto the scene in the two countries. The Brotherhood founded the

Freedom and Justice Party in Egypt, while in Tunisia it formed Ennahda, and both

movements sought to be at the center of the political system, but they failed

to do so.

The Brotherhood is a movement of a religious, doctrinal

nature whose political decision is dominated by a group belonging to the stream

of Sayyid Qutb, who has an overarching ideological nature that calls for a

strong organization that achieves power by controlling the state as the means

of establishing an Islamic state and reinstituting the Islamic caliphate.

Meanwhile, Ennahda has a political essence but is not

doctrinal. It does not divide people into believers and disbelievers, but

divides them according to their intellectual orientations and their political

doctrines: liberal, leftist, secular, Islamist.

The transformation of Ennahda does not refer in any way to

its separation from the Brotherhood, but rather it refers to the current

changes and the failure of the project of political Islam. According to Mourou,

the slogan "Islam is the solution" is an empty slogan that has been used

by peoples unaware of its meaning. He did not provide details of the issues and

alternatives, pointing out instead that the real issue is not undermining

regimes by force, but freedom for the citizens.

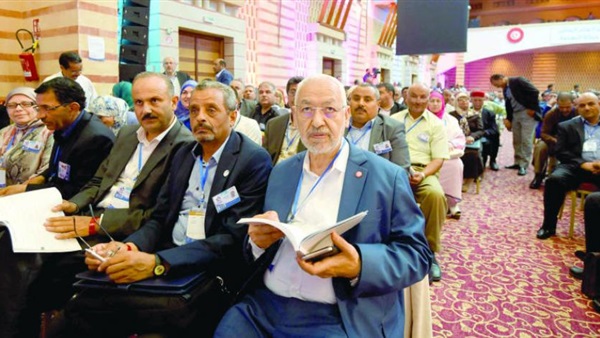

Recently, the Ennahda Movement held a three-day general

conference in which it clearly announced its dissociation from the Muslim

Brotherhood and the inauguration of a new political party bearing the

movement’s name.

The Brotherhood's branch in Jordan is the only one who

welcomed this step, and it may be the next to declare its dissociation from the

Muslim Brotherhood and its transformation into a political party. Meanwhile, the

Brotherhood in Egypt is still in its error, ignoring the conference completely.

The presence of Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi was a

great occasion for the conference, where he delivered a short speech in which

he directed his appreciation to the movement in its decision “to turn into a

civic party away from totalitarianism and monopolization of the religion."

He called on the leadership of Ennahda to prove that they are a civil party

loyal to Tunisia alone and that Islam does not contradict democracy.

Mourou, the movement’s thinker and the godfather of the

transformation, said, "Our battle is against backwardness, division and

terrorism.”

He stressed that “the Islamic movement in Tunisia turned to

constitutionalism” by abandoning the dream of establishing an Islamic state “in

favor of working within the framework of the current political culture that is

subject to the rules of the law.”

Although there is no real separation between the religious

and the political in the minds of the Islamists, this is a procedural method of

employment. Ennahda may have preceded the rest of the groups in removing a

historic obstacle to the Islamists in the path of integration and transparent

political practice based on efficiency and experience, not the claim of purity,

piety and sanctity.

Hassan al-Banna could not solve the jurisprudential and

political problem, because they are practically opposed. The Brotherhood is

immersed in a number of problems and therefore is rejected by all. When it

competes politically, it uses tools that do not exist with the rest of the

political parties and employing the religion politically.

The Brotherhood and other groups have mustered their final attempt.

They are employed in international and regional schemes. They must go back and

solve their problems within modern civil systems, according to the constitution

and the prevailing law.

Without a doubt, Ennahda absorbed what happened to the mother

group in Egypt and was forced to look for solutions. It finally chose to shift

from a strategy of total confrontation with the regime to a policy of

coexistence and positive adjustment, or what could be called “reformist”.

Ennahda’s experiment with governance has contributed to the

disintegration of many of its convictions, including that it was cut off from

society despite its victory, so it decided to be part of the society and its

laws.

Meanwhile, regarding the Brotherhood in Egypt, their plight

is great; more so than the jihadists and Salafis. They are immersed in

calamities and still talking about the rule of democracy and the issue of

identity. They have many years until they transform socially and culturally to

the general purposes of the Sharia, search for solutions to the problems of

society, and work within the project to serve the affairs of citizens, not the

identity project, the discourse of caliphate, or the so-called transition from

the protest phase to the stage of political building and participation.

The Egyptian Brotherhood did not realize this until it was

too late, and then it was completely destroyed.