How is the Politics the only thing can save us?

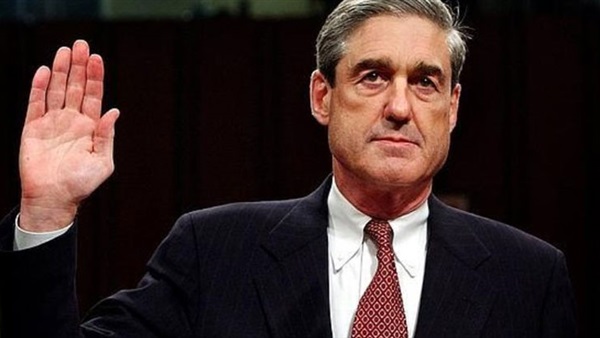

No one would cast Robert Mueller as the lead in a romcom.

And yet watching him deliver a statement on Wednesday regarding his inquiry

into Donald Trump, Russia and obstruction of justice was to experience a

sensation familiar to all romcom devotees.

It comes when the hero needs to reveal his true feelings but

instead becomes tongue-tied. (Hugh Grant built a career on that moment.) You,

the audience, are willing him to ditch the sub-clauses and double-negatives and

just spit it out. You formulate the sentence in your head: it’s simple and

straightforward. But he just can’t get the words out.

So it was with special counsel Mueller. The closest he came

was when he declared that, “if we had had confidence that the president clearly

did not commit a crime, we would have said so.” It was so nearly there, but not

quite. He didn’t say the next logical sentence, which would have been: “But I

could not exonerate him.” Still less did he add the words, “because the

evidence suggests the president did, in fact, clearly commit several crimes”.

Mueller didn’t get that far. He never reached: “I think I love you.”

That left a good part of the audience deflated. They were

hoping for so much more. They longed for Mueller to say it out loud: “Trump is

a crook who should be driven from office.” In fact, they’d been yearning for

that moment of catharsis since the day Mueller was appointed. It was what got

them through this abnormal, abhorrent presidency. They could bear the daily

lies, the routine racism and misogyny, the corruption and the pettiness –

witness the White House order to hide a warship named after John McCain during

Trump’s recent visit to a naval base in Japan, lest the reminder of his late

critic should anger him; they could bear all that, because they thought that

Mueller would one day ride in on his charger and slay the dragon.

A similar fantasy animates the UK’s equivalent of the Trump

presidency, our own populist upheaval of 2016: Brexit. The 8,300 people who

have crowdfunded Marcus Ball’s private prosecution of Boris Johnson also dream

of a courtroom catharsis. This week that prospect became a bit more real, as

Johnson was summoned to appear in court to answer the accusation of misconduct

in a public office when he repeatedly claimed Britain gives £350m a week to the

EU during the referendum campaign.

In both cases, and in others besides, the urge is for the

law to succeed where politics has failed. In Britain and the US, there are many

who believe that Trump and Johnson should pay for their conduct through

ostracism, rejection and loss of power. Instead, they see Trump about to arrive

in London for a state visit, the guest of the Queen, his appalling children

bagging trophy shots of themselves with William, Kate and Harry (though, it

seems, thanks to maternity leave, not Meghan), while Johnson is currently the

favourite to succeed Theresa May as Britain’s prime minister. Far from paying

for their deceits, they profit from them; they are rewarded not with shame and

ignominy, but power.

The fury and frustration this engenders runs wide and deep.

Powering it is anger at a political system that is not doing what it’s supposed

to. Sometimes that sentiment comes from the left, as it does with the

anti-Trump resistance who can read in the US constitution that a president

guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanours” should face impeachment, and yet see

that only around one in 10 members of the House of Representatives are publicly

in favour of starting impeachment proceedings now. Sometimes it can come from

the right, as it does, largely though not exclusively, over Brexit, expressed

by those who say the country voted to leave the EU in 2016, voted again for

parties who promised to leave in 2017, and yet are still waiting. And sometimes

it can come from all sides, as it did this week in Israel, where the voters

went to the polls in April thinking they were electing a government only to see

Benjamin Netanyahu fail to assemble a coalition, thereby triggering a fresh

vote in September.

In each case, the democratic system is failing to deliver on

its promises. And there is the larger, background failure represented by

decades of stagnant wages for most, while the super-rich soared into the

financial stratosphere; the slow, faltering recovery since the crash of 2008;

and the absence of punishment for those guilty of causing that crash. To watch

the National Theatre’s absorbing production of The Lehman Trilogy is to be

reminded that only one US banker – just one, at Credit Suisse – was jailed for

his role in the financial crisis that nearly tanked the global economy. The

number of bankers jailed in the UK? A big, round zero.

Politics finds itself paralysed, pressed between two

conflicting sets of democratic obligations. On the one hand, politicians’ duty

can seem simple: to implement the will of the people. That was the mesmerically

clear message that propelled the Brexit party to first place in last week’s

European elections, demanding MPs “just get on with it” and take Britain out of

the EU as instructed in 2016.

But, on the other hand, in a liberal democracy elected

representatives have other duties too, obligations that don’t always match the

immediate public will. They are required to protect the norms and institutions

that safeguard democracy itself, such as the rule of law, the independence of

the judiciary and a free press. They are required to look beyond partisan

self-interest and protect the national interest.

In the US, that should surely lead the House of

Representatives to do its constitutional duty and, at the very least, open an

impeachment investigation into Trump, with the 10 incidents of egregious

obstruction of justice set out by Mueller as its starting point. Impeachment

may not be politically advantageous for the Democrats, who control the House.

Indeed, it would probably hinder their 2020 campaign, by shifting the focus

away from jobs and healthcare, and help Trump’s, by rallying his base and

allowing him to play the victim. Polling shows no majority demanding it. And

yet, Mueller’s implicit message to Congress was clear: indicting Trump is not

my job, it’s yours.

In Britain, MPs could justifiably say that they are already

doing their duty on Brexit. Yes, they have failed to find the compromise that

would “just get it done”, but that’s because they are tasked with turning an

abstract idea – “Brexit” – into a concrete reality, and there is no specific

form of the latter which commands a majority either in parliament or the

country. It was MPs’ duty to expose that fact, even if it is making them hugely

unpopular in the process.

Implementing the people’s will is rarely as simple as it

sounds, especially when the people are divided down the middle, as Britons are

on Brexit and as Americans are on impeachment. A referendum in a parliamentary

system has paralysed politics in Britain; a rule-breaking, corrupt president

loyally supported by his party has paralysed politics in the US.

There is no lawyer or judge who can get us out of this mess,

however appealing that fantasy might be. We cannot escape the public square for

the courtroom. In a democracy, there is only one jury that can settle these

political battles – and that jury is ourselves.