At five in the afternoon, Cairo time (37).. France’s Decision Against the Muslim Brotherhood: The Beginning of a New European Phase to Dismantle the Organization (2)

In the previous article, we

discussed Europe’s tragedy with the international Muslim Brotherhood

organization and its attempts to take Islam and Muslims hostage in France.

Today, we continue by examining the organization’s strategy, through which it

sought to penetrate French society by multiple means—economically, socially,

intellectually, and organizationally. Unfortunately, the organization benefited

from every step taken by successive French governments to recognize it as a

representative of Islam and Muslims in France.

This occurred after the 2003

Sarkozy project, which granted representatives of the group the right to

represent Muslims in France before the French authorities, through free

selection via mosques and federations. They then began striking deals with

specific countries to finance the construction of major mosques, considering

them the gateway to leadership and representation of Muslims.

They also began forming

associations and federations that enabled them, through their representatives,

to exercise full control over the newly established council, which became the

sole legitimate representative of Muslims in France.

Former French President Sarkozy

gave the Muslim Brotherhood the legal instrument to hijack Islam and Muslims in

France in broad daylight. They restructured their organizational frameworks to

become a state within a state, capable of using their representation of Muslims

for the organization’s separatist purposes.

For all these reasons, the only

solution to dealing with this crisis—from our point of view, and as we have

proposed in more than one conference and public discussion session in France,

whether within the National Assembly, the Senate, or even the European

Parliament in Strasbourg—is to begin confronting this Brotherhood organization

and its French branch, “The Union of Muslims of France,” by dismantling its

structure, drying up its sources of funding, and banning its associations.

None of this can be achieved

without criminalizing the organization and stripping it of legitimacy by

classifying it as a terrorist entity.

Otherwise, the French will find

themselves going in circles, returning each time to square one to start all

over again—precisely what happened in all the experiences mentioned earlier.

But how does the dismantling

process take place?

Dismantling the Muslim

Brotherhood organization that has hijacked Islam and Muslims in France is not

achieved solely by banning its structures and associations and drying up its

funding sources, but also by refuting the ideas it uses to recruit its members.

For this strategy to succeed,

those implementing it must adhere to four basic principles:

First: Avoid conflating Islam as

a religion with the organization that hijacks it, and deal with the crisis as

one of organized abduction of the Islamic religion, not as a structural crisis

inherent to Islam or Muslims.

Second: This approach must avoid

the discourse of victimhood and Islamophobia, which Brotherhood cadres,

leaders, and media mouthpieces will quickly resort to in response to such

measures.

Third: The confrontation must be

conducted on the basis of societal unity among supporters, citizens, and

politicians of the French Republic. It is neither permissible nor appropriate

for this confrontation to be undermined by any form of political infighting

among rival French political parties and currents—from the far left,

represented by the French politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who adopts the

Brotherhood’s victimhood narrative, to the far right, represented by Marine Le

Pen, who at times demonizes Muslims themselves. This issue is, quite simply, a

matter of national security for France first and foremost, just like the issue

of terrorism and the use of violence against peaceful citizens.

Fourth: Refrain from addressing

the issue of building “Islam in France” in the same way the Jewish model was

handled in 1806, as doing so would be akin to “using a unit of distance to

measure density.”

The Beginning of the Brotherhood

Threat

France today stands at a

crossroads after the government decided to confront the Muslim Brotherhood

decisively, and after parliament issued its long-delayed decision—at least ten

years overdue—to classify the organization as a terrorist entity. This entails

banning its activities and associations, drying up its funding sources, and

pursuing its leaders and cadres.

The international organization

arrived in France in the 1980s with a single objective that the Brotherhood at

the time termed “empowerment in the West.”

This empowerment, according to

their vision, is achieved through three stages that operate in parallel rather

than sequentially.

First: Social Empowerment

This is achieved through

establishing social institutions through which French Muslims and immigrants

are gathered and organized into structured administrative units. The process

began with seven associations in 1989, growing to 250 associations by mid-2005,

and has now reached more than 500 associations and institutions at the time of

the decision.

Second: Economic Empowerment

This takes place through direct

and indirect funding. The latter consists of diplomatic moneybags used to build

mosques, schools, cultural centers, and a number of other educational

activities. Direct funding comes through donations and bank transfers, in

addition to revenues from Islamic activities such as halal trade, Hajj and

Umrah services, and the collection of zakat and alms.

Third: Cultural Empowerment

This is achieved through

establishing cultural centers and schools, and approving and supporting private

education and homeschooling, which allowed the Brotherhood to disseminate its

intellectual and religious educational doctrine throughout these suburbs.

These three forms of empowerment

lead to political empowerment, which usually begins with influencing local and

general elections and develops into an important card that politicians must

take into account in their electoral battles—eventually reaching a stage where

the Brotherhood becomes a decisive factor in any legislative or presidential

election.

This occurred in the most recent

legislative elections in France, where the leader of the French left-wing

alliance, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, outperformed with the votes of Islamists.

Based on these conclusions,

dismantling this organization in all its social, economic, and cultural

manifestations becomes an urgent necessity, especially after its designation as

a terrorist entity by the French parliament.

Naturally, the new decision will

contribute significantly to this dismantling process, but it will not be

sufficient on its own. The Brotherhood organization is known for its ability to

adapt to all circumstances and its skill in overcoming the obstacles it has

faced throughout its history. For nearly a hundred years, the Brotherhood has

succeeded in exploiting the contradictions of its opponents to its advantage

and building its institutions through them—the Egyptian experience is the best

proof of this.

Dismantling Is a Complex Process

If France is serious about

dismantling the organization after banning it, it must first give the highest

priority to drying up funding sources, monitoring and banning them, and

prosecuting those responsible. These are the primary weapons that must be used

to initiate the next decisive step: dismantling the ideological system that the

group has succeeded in embedding within French society through its schools,

mosques, and associations.

This type of ideological

dismantling will require years of work to achieve positive and decisive

results, because France is now facing a complex process of construction,

penetration, and infiltration by the Brotherhood organization that has

continued for many years.

The Octopus

In 2009, specifically after

Egyptian security services arrested a number of Brotherhood leaders and cadres

and brought them to trial in what became known in the media as the

“International Organization Case,” Egyptian security services were able to

examine the group’s strategy of infiltration through soft power in Egypt and

around the world.

I had an appointment with the

general responsible for the Muslim Brotherhood monitoring department within

Egypt’s State Security Investigations Service, who supervised the investigation

reports related to the case. I was surprised when he abruptly asked me: Do you

believe that the members of the group’s Guidance Bureau, whose names and

capabilities we know well, are the ones who manage this octopus-like

organization on a global level?

I replied: If not them, then who,

in your view, manages this organization?

The man responded: I do not have

specific information, but based on my close knowledge of the capabilities of

these individuals, I can tell you that they are incapable of managing a

medium-sized company—let alone this enormous organization spread across nearly

half the globe.

His question and answer did not

surprise me much, because I had always been convinced that in Egypt we look at

only one face of the Muslim Brotherhood: the hierarchical organization composed

of the General Guide, the Guidance Bureau, and the Shura Council. This face of

the organization represents, so to speak, a “brand,” analogous in the political

sphere to a constitutional monarchy—where the family owns under this system,

while actual governance is in the hands of parallel political forces that hold

the majority in one way or another and rotate power in accordance with the

constitution.

I had observed and analyzed this

transformation in several of my studies, the most important of which are The

Secret Files of the Brotherhood, The Crisis of the Renewal Current, and The

Brotherhood State, among others.

From my point of view, thinking

about this transformation from a hierarchical system to a network system began

long ago, when the group was first struck in 1948 by the government of Ibrahim

Pasha Abdel Hadi, leader of the Constitutional Liberals Party in Egypt, in

retaliation for their assassination of then–Prime Minister Mahmoud Fahmy

El-Nokrashy after he decided to dissolve the group in response to its terrorist

operations inside Egypt.

Those events, which ended with

the killing of the group’s founder and General Guide Hassan al-Banna, marked

the true beginning of thinking about transitioning from the concept of a

hierarchical organization with a single, clear head—while maintaining it in a

number of countries, including the country of origin, Egypt—to the concept of a

network resembling an octopus with multiple arms.

Then came Gamal Abdel Nasser’s

crushing blow to the group in 1954, which accelerated the adoption and

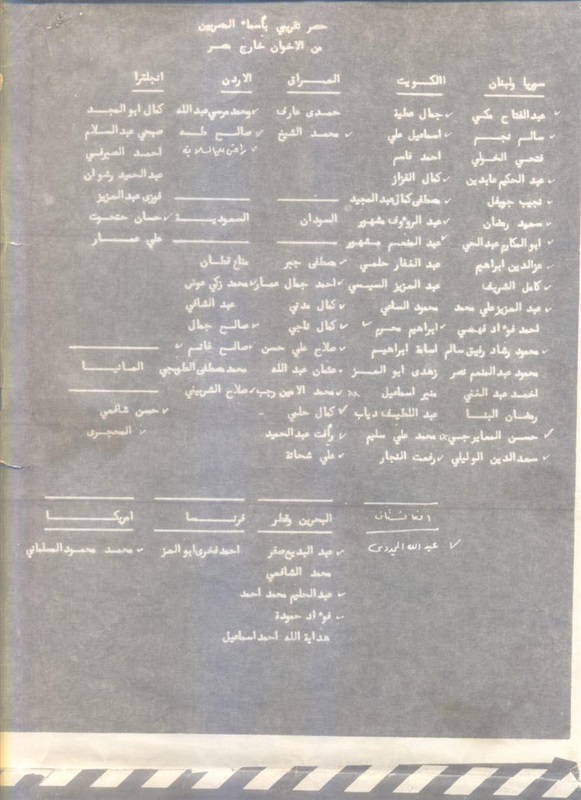

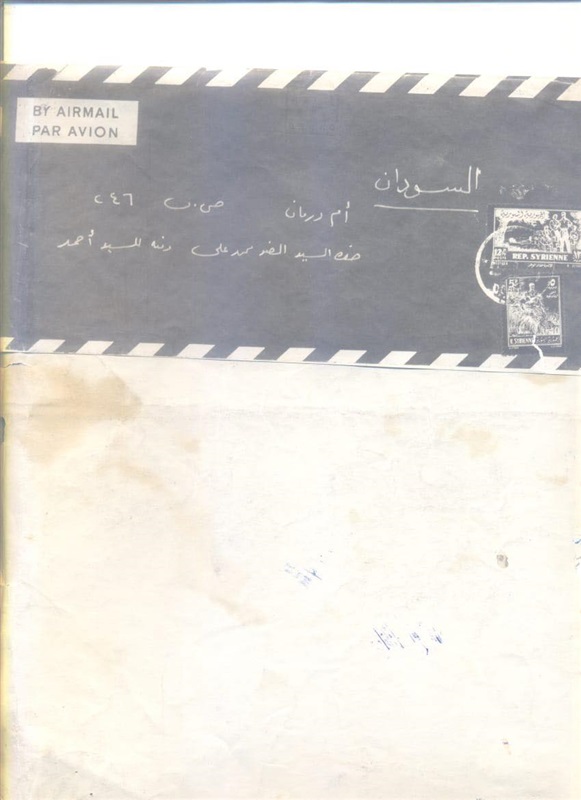

implementation of this option. We later found an old letter bearing the

postmark of Omdurman, Sudan, containing the names of the group’s temporary

leadership during the years of ordeal. All of them were unknown to the regime

or the security services in Egypt at the time; some were even considered by the

regime to be among its supporters. Strangely, all of them were living outside

Egypt. (An image of the document is attached.)

Tomorrow, we continue.

Paris: 5:00 p.m. Cairo time.